Basic Linguistic Concepts for Cherokee Language Students

Learning Cherokee can be uniquely frustrating, because when students get confused, they often struggle to understand what it is that’s confusing them in the first place. Students often feel completely unable to articulate their confusion, or ask the kind of useful questions that will actually clarify that confusion. This kind of frustration, in my opinion, is greatly reduced by just a smidge of context from the field of Linguistics.

Disclaimer: I have no credentials at all in Linguistics. It’s been an interest of mine for a while, since long before I ever started seriously studying Cherokee, but I am not a Linguist. Beyond that point, I’m trying my best to keep this essay as simple and accessible as possible. So keep in mind: I’m not a Linguist, and I’m presenting Linguistic topics in an extremely surface-level way in this essay.

What is Linguistics?

Linguistics is the general study of languages. Not the study of any one particular language, or how to speak any particular language, but the study of language itself. It seeks to answer questions like: How do languages work? How can languages be classified? How do languages evolve? How do different languages form and use words? So on and so forth. Linguistics is one of the “soft sciences” or Liberal Arts, like Anthropology or Sociology.

Like any academic field, there are many, many sub-fields and branches of Linguistics. For our purposes today, the most important of these sub-fields is Morphology.

Morphology and Important Terms.

Morphology is the sub-field of Linguistics that focuses on how “words” are formed. The definition of what is or is not “a word” is debated within Linguistics—apparently, it’s a pretty difficult question to answer. We’re not going to get too far into that issue—for our purposes, all you need to know is the difference between “words” and “morphemes:”

A “morpheme” is the smallest possible unit of speech that carries meaning. It cannot be reduced to any smaller parts without losing that meaning.

A “word” is the smallest possible unit of speech that can stand on its own. It may be reducible to smaller parts, because words are sometimes formed from multiple morphemes—but not always.

These categories are not mutually exclusive. The best way to explain this is by example. Here are two distinct English morphemes:

If you put these two parts together, you get a new word—cats. This new word contains two morphemes, /cat/ and /s/. So, some morphemes are words, but some are not. Many words contain multiple distinct morphemes, and sometimes the “morphemes” contained within one word are also distinct words themselves. The categories overlap, and it’s not clear where one ends and the other begins, is what I’m trying to convey.

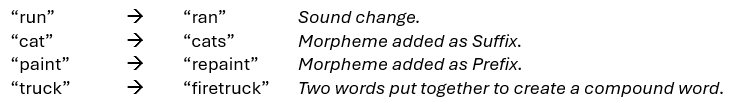

For our purposes, the most important thing to remember is the “morph” part of all this—the study of Morphology is the study of how words are formed, yes, but you could also think of it as the study of how words can change, morph. The study of how words are built and changed. This process of changing words to create or modify their meaning is called “inflection.” Inflection can occur through changes in pronunciation, adding or subtracting morphemes from a word, or putting entire words together to create new “compound words.” For example:

The “cats” example is the simplest one I can think of in English, but there’s no limit to it. Consider the following word “antidisestablishmentarianism.” We can “parse” (dissect the word to examine its parts) as follows:

So the resulting word, “antidisestablishmentarianism,” is made of at least six discreet Morphemes, and the resulting word basically means a belief characteristic of one who opposes the disestablishment of institutions, or a belief against the unmaking of institutions.

Inflection frequently involves “Affixes,” which are non-word Morphemes that must attach to other words or word parts to be used. There are a few different kinds of Affixes: 1) Prefixes, which come at the beginning of the word to which they attach; 2) Suffixes, which come at the end of the word to which they attach; and 3) Infixes, which come in the middle of the word to which they attach.

In our earlier “cats” example, the Anglo-Saxon /s/ is a Suffix. In the word “unmake,” /un/ is a Prefix. It’s hard to come up with an example of an Infix in English. The closest I can think of is the use of “fucking” in the middle of another word as an intensifier, as in “fan-fucking-tastic.”

If you’ve ever studied Spanish, you’ve probably heard the term “conjugate.” “Conjugation” is a word used to describe processes by which verbs can be inflected.

I’ve thrown a lot of new vocabulary at you here, so let’s bring it all together with a quick review before moving on: Morphology is the study of how words are formed. The word formation process involves both “words” and Morphemes. Words carry meaning and can stand on their own. Morphemes carry meaning but cannot stand on their own, unless they also happen to be words—the categories are not mutually exclusive. The process by which words can be “morphed” to change their meaning is called Inflection, and it frequently involves adding other words or Affixes (such as Prefixes, Suffixes, or Infixes) to existing words. “Conjugation” is a word that refers specifically to verb inflection.

Morphological Classification.

Not all languages use these “morphological processes” equally. Some languages inflect words more than others. Some languages barely inflect words at all. This diversity allows us to classify languages on a morphological spectrum from “less inflection” to “more inflection”—languages whose words change frequently, and languages whose words don’t change very much.

Languages with more inflection are called “Synthetic” languages. Synthetic languages make wider use of inflection, and words can morph to take many different forms and meanings. This means individual words can be specially crafted to carry more precise meanings. These languages generally have more flexible word order and a lower reliance on helping words.

Languages in which inflection is less common (or uncommon) are called “Analytical” Languages. Analytical languages don’t use word-morphing processes as much—instead relying more on helping words and word order rules to provide the same precision that comes from inflection in Synthetic languages.

You are likely to hear these ten-dollar Linguistic phrases used in a lot of different ways. For example, language processes characteristic of Synthetic languages—Inflection by use of Affixes, for example—can be called “Synthetic Processes.” A word that is produced by applying many “Synthetic Processes” may be called a “highly Synthesized” word.

On the other hand, if a phrase or expression relies on word order or helping words to be understood—qualities characteristic of Analytical languages—that phrase may be referred to as an “Analytical Construction.”

Just keep the following rules-of-thumb in mind:

- When you hear the word “Synthetic” (or any other forms of that word) in the Linguistic context, think about inflection—words that change. Sound changes, Affixes, compound words, etc.

- When you hear the word “Analytical” in the Linguistic context, think about unchanging word forms, and especially think of word order and helping words.

Now we'll go a bit more in-depth:

Synthetic Languages.

Synthetic languages are characterized by a higher prevalence of Inflection to modify word meanings, meaning highly modified words with extremely specific meanings become possible. When words carry their own specific meanings with a high level of precision, word order becomes more flexible. There’s a reason for this, and we’ll explore it more later.

Synthetic languages tend to present more challenging rules regarding words themselves and how they must change to communicate specific meanings. Words can change a lot. Inflective processes often involve sound or spelling changes that can cause a word to look or sound completely different from one situation to another. On the other hand, you don’t have to worry so much about word order rules or helping words (which tend to be lexically strange and difficult to translate). Building words is more complicated, but building sentences is simpler.

Examples of Synthetic Processes:

Analytical Languages.

Analytical languages are characterized by a lower prevalence of Inflection to modify word meanings, resulting in a much greater reliance on word order and “helping words” to clarify the interrelationship of words within a phrase or sentence. Analytical languages require you to learn elaborate word order rules and a large vocabulary of “helping words” and how to use them—but words usually come in one form and one form only, making them easy to learn and recognize. Sentences are more complicated, but words are much, much simpler.

Examples of Analytical Processes:

Notice how I’ve given examples of both Synthetic and Analytical processes in English and Spanish. This brings us to an important point: no known language on earth is purely Synthetic or Analytical. All languages have some mixture of both—whether a language is classified as one or the other is based completely on which way the language leans. Which kind of process is more common—that’s all it means to say a language is either Synthetic or Analytical.

The Relationship Between Inflection and Word Order.

It’s come up multiple times already: the more Synthetic a language is, the more flexible word order tends to be. But why? The relationship between inflection and word order is not obvious, but there is a good reason for it. Old English (the English spoken by Anglo-Frisian tribesmen in the year 700 AD and the English of Beowulf, but not the English of Shakespeare, which came much later) provides the best example of this phenomenon I can think of.

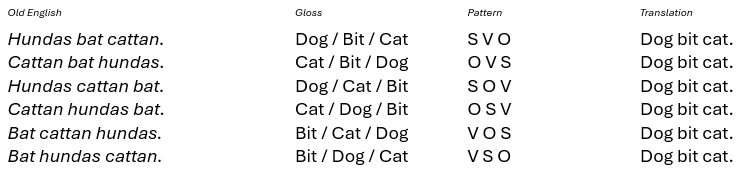

Old English used to have something called “Case.” “Case” in Old English is a system of inflecting nouns to encode subject/object information. That’s a fancy way of saying nouns could be inflected to indicate whether the noun is the one doing an action (the Subject of a verb) or the one receiving the action (the Object of a verb).

The Old English word for “dog” is hund. If a hund is the one acting (the Subject), it is inflected with the Case Suffix /as/--creating a newly synthesized word: hundas.

On the other hand, if a hund is the one being acted on (the Object), it receives the Case Suffix /an/, creating hundan.

So if you see the word hundas or hundan, you can already tell whether a dog is acting or being acted on without any additional context whatsoever. You don’t need to know any other actors, or even what action is being done. Just by looking at the word and recognizing its Case, you know who’s acting and who’s being acted on.

Because the nouns speak for themselves, word order suddenly doesn’t matter. In Old English, you can put nouns in any order relative to a verb and the sentence will still make sense. The nouns, by themselves, can tell you who’s doing what to whom, so you don’t need word order to provide that clarification. See:

The meaning of this sentence stays completely unchanged and totally clear, no matter how you arrange the words. Clarity is provided by Inflection. The words “speak for themselves.” But how does this work in Modern English?

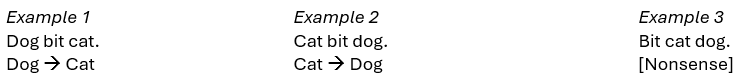

Over the years, English has lost this system of Case Inflection. Because we can no longer distinguish Subjects from Objects by Case, we now use word order. Modern English uses a standardized word order rule to clarify Subject and Object relationships—and that word order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO).

Whichever noun comes first is the Subject by virtue of coming first. The verb comes next, and whatever noun is placed after the verb is automatically understood as the verb’s Object. Based on the order of the words relative to one another, we know who is acting on whom. We no longer need to remember or use Case Suffixes, but now we must strictly follow a specific word order pattern. We no longer have the flexibility shown in the Old English, because changing the word order results in completely changing the meaning of the sentence—some word orders even resulting in complete nonsense. Compare:

So, hopefully this illustrates the relationship between inflection and word order. Synthetic Processes tend to diminish the importance of word order, so Synthetic languages tend to have more flexible word order. Analytical languages need stricter word order rules to help provide the clarity that would otherwise come from inflection in a Synthetic language.

Beyond Synthetic and Analytical: Polysynthetic and Isolating Languages.

Earlier, I said that no language is purely Synthetic or Analytical. That’s still true. That said, there are languages that lean so extremely towards one or the other that it justifies creating completely new categories to help us talk about them. These are the Polysynthetic languages and the Isolating languages.

Polysynthetic languages and their characteristics.

Polysynthetic languages are the most extreme examples of Synthetic languages. These languages are characterized by a high prevalence of Inflective processes used to create absurdly specific, often very long words containing a very high number of discreet morphemes. Often, Polysynthetic languages are capable of synthesizing single words that can function by themselves as complete sentences—even long sentences. Here’s an example I found on the Wikipedia article for “Polysynthetic language”—this is a single word from the Yupik language, and its meaning in English:

The Inflective processes of Polysynthetic languages are so extreme they complicate our understanding of what a “word” even is. Polysynthetic languages provide the best illustration of why such a simple-seeming question as “what is a word” has proven to be so difficult for academic linguists. That Yupik example above. Is that a “word?” Is it a sentence? At what point do these distinctions cease to be meaningful? I bring it up here as food for thought—the process of learning Cherokee will be much easier if you learn now to have a flexible idea of what a “word” is, or can be.

Characteristics of Polysynthetic languages. Polysynthetic languages are typified by an extremely high ratio of morphemes-to-words (that is, individual words tend to contain a very high number of morphemes). Word order is extremely flexible, often amounting to little more than a matter of style. Verbs tend to be especially important in Polysynthetic languages. These languages often have astonishingly complex Synthetic systems for verb conjugation, and precisely crafted verbs often carry most of the meaning of any given phrase or sentence. Other than verbs, other “word categories” can become difficult to clearly identify—just like the distinction between “words” and “sentences,” the lines separating “verbs,” “adjectives,” “adverbs,” “nouns,” etc. tend to be pretty blurry.

When people think of Polysynthetic languages, they tend to think most about the indigenous languages of North and South America. Many, many American languages are classified as Polysynthetic, including such diverse examples as Inuk, Navajo, Cree, Nahuatl, and—yes, Cherokee.

Isolating languages and their characteristics.

These are the most extreme examples of Analytical languages. These languages are characterized by a near-total absence of any kind of Synthetic inflection. Verb conjugation in any form is often completely absent. Instead, such languages are characterized by extremely elaborate word order rules and an extensive inventory of helping words. Isolating languages (and other Analytical languages) tend to have much clearer distinctions between different word types—verbs, nouns, adjectives, tend to be clearly distinguished from one another, so words tend to be easily classifiable by type. This, of course, is a necessary complement to the importance of word order. Word order rules frequently turn on the axis of word type—“adjectives come before nouns they modify,” “subject-verb-object,” and so on.

Isolating languages are typified by a 1-to-1 or nearly 1-to-1 ratio of words-to-morphemes. This means that words with more than one morpheme—words like “cats”—are nearly nonexistent in an Isolating language. Almost every word communicates precisely one idea, and the only way to change or modify a given word is by putting other words around it in a carefully crafted order. Many Asian languages are classified as Isolating—Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, Khmer, and Lao are all Isolating. Some West African languages like Yoruba also fit this category.

I will not be elaborating on Isolating languages further. Luckily for you, Isolating languages have basically no relevance to your task of learning Cherokee. I only brought it up because I couldn’t talk about Polysynthetic languages as the “most extreme” Synthetic languages without folks wondering about the “most extreme Analytical” languages.

Moving on!

Why is this Relevant? Providing Context for your Language Learning.

Generally speaking, it’s easier to learn languages that have a lot in common with your native language. On the other hand, it tends to be harder to learn languages the more they differ from your native language. If you, an English speaker, were to sit down to study Dutch, Afrikaans, Frisian, or Old English, you might be surprised how easy they are for you. Those languages are very closely related to yours. On the other hand, the more a second language differs from yours, the harder it’ll be for you to learn it.

When you are learning a new language and encounter something particularly challenging to learn or understand, you can probably bet that it’s because the same topic is handled very differently in your own language—or because you’re dealing with a process in the second language that simply does not exist in your language. Sometimes it can be difficult to even recognize what it is you don’t understand, or articulate what it is that’s caused your confusion. A lot of this, ultimately, is caused by the way we take the grammar and structure of our own language for granted—we speak and understand our own language intuitively, rather than intellectually. You know your language, but most of us can’t really explain our languages. So when you encounter something in a new language that’s very different from you own, sometimes you don’t even recognize how it is different, and therefore cannot articulate the source of your confusion. But if you learn to intellectualize your own language, you could say “well, this topic in my studied language is confusing to me because it seems very different to how we do it in English, which is like so.”

This is why obtaining a basic understanding of simple Linguistic concepts can be so helpful for you as you go on to study Cherokee, and why I’ve written this essay to introduce you to these ideas. Knowing basic Linguistics will help you “orient” yourself as an English-speaking Cherokee language student. It will defang some of that frustrating confusion—it will help you to identify problems and explain yourself when you become confused, giving you a better chance to recognize what it is that’s confusing you. It won’t save you from encountering confusion in your learning process, but it should stop confusion from sticking so much. When you get lost, knowing why and how you’re lost is half the battle won already.

So let’s get you oriented here—you are an English-speaking Cherokee language student:

English, the language you speak, is generally considered an Analytical language. It’s in the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. Its Analytical nature is pretty unique among European languages. Most European languages (including other Germanic languages) are somewhere in the middle of the Morphological spectrum, but tend to lean Synthetic. English is in the middle leaning Analytical—leaning pretty hard towards Analytical, at that.

As mentioned before, English used to be much more Synthetic, but it’s lost most of its Synthetic processes over time. English verb conjugation is minimal. It only has one truly Synthetic verb tense—the Past Tense (“run” to “ran,” for example). Instead, it uses helping words (almost always a form of “to be” placed before the verb, as in “run” to “will run”) to form most verb tenses. Inflection is more common with adjectives (as in “big” to “bigger” to “biggest”), but overall word order and correct usage of helping words “rules the roost” of English grammar. In many ways “English grammar” is synonymous with English word order rules. Because of this, you are not well-versed in changing words to create new meanings, or creating new words whole-cloth. Inflection and non-standardized word order will probably be generally uncomfortable for you.

The best examples of Inflective processes in English are found mostly in loan words from other, more highly Synthetic languages. English vocabulary borrows heavily from Latin and Greek. We didn’t just get words from those languages, we also borrowed a huge inventory of prefixes, suffixes, and so. Some of those Affixes have become widespread in the language, but for the most part they’re associated with highly technical language. English inflection is at its most elaborate in “ten-dollar words” used by dweebs in fields like Science and Politics—words like “antidisestablishmentarianism,” “morphologically,” or “ribonucleic.”

You aren’t in the habit of making up new words on the spot. In fact, English speakers often laugh at “made-up” words—the very idea of “making up words” seems silly to English speakers. Dr. Seuss-isms. Yuzz-a-ma-tuzz. Loopdyloops, flibbertygibbits, and so on. Superblueification (the process of causing something to become extremely blue, obviously). Necropocalypticon (of course, a foul tome of world-ending death magicks).

On the other hand, English-speaker, you’re very well-versed in observing strict word order rules and the use of helping words. Your brain is trained to look for words with predictable, unchanging forms that you can memorize as-is and plug directly into a predictable system of word order rules. JW Webster refers to this as a “plug and play” process—referring to the “plug and play” video game toys that were popular in the 2000s. Learn the word as it’s presented, then plug it into the sentence you’re building at whatever specific point such a word is meant to go. You could also compare it to the “peg-and-hole” toys we give to toddlers for teaching shapes—the square peg goes into the square hole. When you have a “verb-shaped” word, you look for a “verb-shaped” hole for it in your sentence. Your brain searches for clean-cut rules about word type and word order.

Verbs (actions) are less emphasized in your language than are nouns (things). You expect grammar to work like a blueprint, instructions on how to put pieces together. But importantly, you aren’t used to building words—you build sentences by gluing words together with helping words. You’re comfortable using helping words even when you barely know what they mean. Could you explain, right now, the difference between “the apple” and “an apple?” Could you give me a dictionary-type definition of “either?” While we’re at it, what about “while?” You may be surprised by how difficult it is to “define” words like these now that you’ve been asked to do it. But it’s never once stopped you from using or understanding them, has it? (By the way, in the sentence immediately preceding this one—what does “from” mean?) Because you speak an Analytical language, you are comfortable using a word based solely on an intuitive understanding of how the word is used, where it fits in the sentence blueprint. You are good at intuiting the function of words, as long as you can recognize them in familiar forms, roles, or patterns.

One last thing—as an English speaker, you are not comfortable using tones to express grammatical or lexical information. I’ll unpack that in just a second. First, I want to dispel a misconception. English speakers talk about “tonal” languages like they’re the most intimidating thing imaginable—but English is a tonal language. Why do you think I use italics so much when I write? Because it’s the easiest way to capture the tonal element of English in writing. We use tones all the time in English. So why isn’t English generally classified as a “tonal” language, like Mandarin or Thai? Unlike those languages, English tones do not carry “lexical” or “grammatical” meaning.

The languages that usually get called “Tonal” are languages that use Lexical Tones, Grammatical Tones, or both. “Lexical Tones” are tones that help speakers distinguish between words that would otherwise sound identical. “Grammatical Tones” are tones that carry grammatical information—tones that indicate verb tense, or tones used as a tool of inflection. English does not have those kinds of tone. English tonality is “free form,” used entirely as an expressive tool—not to express translatable meaning, but to express feeling, add emphasis, or clarify the intent behind a statement. The best example is one you may have seen before: the English sentence “I never said she stole that car.” The feeling of the sentence completely changes based on which word is tonally stressed. Compare:

So, let’s be clear—you are accustomed to “using tone.” But you are not accustomed to using Lexical or Grammatical Tones. You are likely to feel extremely restricted by that kind of tonality, because you are accustomed to tonality as a totally unbound tool of expression, not a tool of grammar.

This brings us to Cherokee:

Cherokee, the language you are learning, is a Polysynthetic language. It is in the Iroquoian language family. Its closest relatives come from the Great Lakes region—languages like Mohawk, Onandaga, and Seneca-Cayuga. It’s the only living member of the “South Iroquoian” branch of the Iroquoian language family, while the Great Lakes Iroquoian languages are called “North Iroquoian.” In this way, Cherokee is unique. When people think of tribes “closely related” to the Cherokees, they probably think of other Southeast Woodland tribes like the Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Nations. And sure, there’s a lot of common ground between these tribes in terms of culture and history—but in terms of language they are basically unrelated. The other Nations in the “Five Tribes” speak Muscogean languages, a totally different language family. Linguistically, Cherokee is more closely related to the Mohawk spoken in New York than to the Muscogee (Creek) language spoken in Oklahoma. All these languages—whether Iroquoian or Muscogean—are Polysynthetic.

In Cherokee, you’ll build words more than you build sentences. It is very normal for people to use words you’ve never heard before, because people make words up on the spot to suit their needs—but these “made-up” words are not “Seuss-talk,” or “slang,” they’re a core feature of the language. Cherokee grammar is synonymous with the Cherokee word-building system, and individuals have a high level of flexibility in how they build and use their words, even as a matter of personal preference and style. You could think of the Cherokee language as one big word-building engine.

This is a problem for English speakers, who are accustomed to imagining languages as a list of “plug and play” words with a set of word order rules. You are used to words that work like bricks to be placed in a specific position according to a blueprint. You want “verb-shaped” words to fill “verb-shaped” holes. But Cherokee words don’t come in standardized “shapes,” so to speak. Cherokee words are flexible, moving, fluid things—even simple nouns come in so many forms that it becomes difficult to define where the word begins and ends:

So what is the Cherokee word for “mother?” Maybe you’d say it’s the Root itself, / ji2 /, but that’s not a word. It’s just the Root—it requires inflection before it becomes intelligible as a word. But on the other hand, many of those “words” could be translated as whole phrases—so what are they? You need to get comfortable with ideas as fluid things that can take the form of many distinct words—even ideas as simple and familiar as “mom.” This is especially, almost absurdly true for verbs and words built from them. All of the following words are built from exactly the same verb root:

These words mean, in order:

- S/he is conversing

- If you and I will be conversing

- Phone, n.

- Go converse with him/her!

- Conversation, n.

I compared English sentences to a thing that is built according to a blueprint. Cherokee sentences orient words together more like a flowchart—words gesture to each other, constantly defining and redefining other words around them by contextualizing and recontextualizing them. Sentences are not structured ideas but ideas in motion. Word order in Cherokee is extremely flexible. In fact, Cherokee Syntax (word order) is about as flexible as English tone—and in fact, they are used for basically the same purposes (mostly emphasis). Look how the meaning communicated in English by tonal inflection is accomplished in Cherokee by word choice and word order:

Cherokee includes both Lexical and Grammatical Tones—it is a “Tonal Language” in the purest sense. This is likely to be uncomfortable to you as an English speaker for all the reasons we discussed above. When you are deprived of tonality as a free-form, emotionally expressive tool, you are likely to feel very limited in your ability to express yourself. But, as I illustrated above, there are other ways to express yourself. In Cherokee, that’s going to mostly be word choice and word order.

A final, related point—learning correct pronunciation is extremely important in Cherokee. Have you ever heard a foreign person speak English very well but with an extremely thick accent? You could probably still understand them perfectly, right? Cherokee does not work that way. Correct pronunciation, including things like vowel length and especially tone, are absolutely critical to Cherokee comprehension. I’m going to assume you’ve seen King of the Hill—remember how Peggy Hill speaks Spanish? You cannot speak Cherokee Peggy Hill-style. I tell you this now so you don’t neglect it. Practice listening to Cherokee and repeating the sounds you hear, including tonal shifts—it’s crucial. In the early phases of my learning, I would even “babble” to myself when I was alone in my car—just sit there babbling nonsense to myself like an idiot, but trying my best to make it sound like Cherokee I’d heard. When you listen to Cherokee speech, try to take note of sounds you hear repeated a lot. Practice making those sounds by babbling. As silly as it seems, I believe this practice was priceless to my ability to pronounce Cherokee sounds. In class, when you’re repeating words the teacher says, it is not good enough to just flatly repeat the syllables you hear. You need to listen closely to the rhythm of the word, the musicality of the word, and try to match it. Think of it as learning to “sing” the words, instead of just learning to say them.

Speaking of babbling, I seem to have wandered off topic. Let’s wrap it up:

Conclusion

You are undertaking to learn a language profoundly different from your own. This presents a big challenge—but remember, we don’t dwell on the difficulty of it, we resist discouragement, and we keep at it. Difficult things get done all the time, and having this foundation of Linguistic knowledge and a more objective understanding of your own language should help you push through confusion when you encounter it. Whenever you find yourself stuck on something, just not getting it, take a second to step back and ask yourself how the topic works in your own language. If you’re stumbling over something, it’s probably because you are encountering something that feels alien, something that works very differently from Cherokee to English. The stumbling block is likely to be something about inflection—like failing to recognize a root because of some sound change rule you don’t have pinned down. Maybe you’re getting lost because you’re struggling to conceptualize the fluidity of Cherokee words or word order. Maybe you’re missing some specific detail about how words in a sentence relate to and change one another based on their position in the sentence.

Sometimes, Cherokee may seem like a mysterious maze of impossible rules—something totally alien. But it’s not. There is nothing arcane, alien, or exceptionally difficult to understand about it, objectively speaking—it only seems that way to you because you are English speaker. It is never as scary or as strange as it seems, and if you practice de-centering English and learn to look at both languages from a more objective Linguistic perspective, you will empower yourself to push through your English-speaking limitations and overcome confusion much more efficiently.

By: J.R. Lancaster a second-language learner. May contain mistakes.

Add comment

Comments