Introduction to Cherokee Stem Forms:

Incompletive, Completive, Immediate, and Infinitive

By now you’ve probably heard terms like “Incompletive,” or “Completive.” Some sources call these categories “Aspects.” Some use the terms without ever explaining what they are or what they mean. But basically every source addresses these categories using the same five labels—“Present Continuous,” “Incompletive,” “Completive,” “Immediate,” and “Infinitive.”

But what are they?

Verb Stems and Stem Forms

A Verb “Stem” is the Verb Root plus a Root Suffix (or an Adverbial Suffix Stem, but forget about that for now). Every Cherokee verb has up to five distinct Stems. These distinct Stems are called “Stem Forms.”

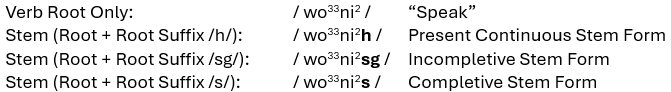

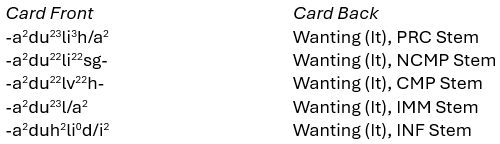

Each of a verb’s Stem Forms fall into one of the following categories: 1) Present Continuous (PRC), 2) Incompletive (NCMP), 3) Completive (CMP), 4) Immediate (IMM), and 5) Infinitive (INF). Usually the only difference between one “Stem Form” of a verb and another is which Root Suffix is used. For example:

It is important to learn how to isolate the Stem Forms of Cherokee verbs, because the different Stem Forms frame the verb’s action in different ways and provide the first building block of Cherokee verb tenses. Many of the different ways Cherokee verbs can be used are based first on what Stem Form is used, and changing the Verb Stem often changes the meaning of a fully conjugated verb in a big way. So what’s the difference between these Stem Form categories in terms of meaning? What do Stem Forms “do” for Cherokee verbs?

Stem Forms “contextualize” the verb action in different ways. The different Stem Forms “frame” verb actions in different ways. More specifically, each Stem Form contextualizes the way the speaker is describing or depicting the status of the verb action in a unique way. It’s less about the reality of how the action occurred or didn’t occur, and more about how the speaker is choosing to describe or frame that action in speech.

Stem Form is closely related to verb Tense. “Tense” is a part of grammar you’re probably already familiar with—it’s the part of a verb that tells you when the action is occurring. Present, Past, Future, and so on. In Cherokee, Stem Form establishes certain aspects of how the speaker means to describe the action before it is placed into a specific timeframe by a Tense Suffix. The same verb, with the same Tense Suffix, will be translated differently based on which Stem Form is used:

Note the difference in how those verbs are translated—despite having the same Pronomial Prefix and the same Tense Suffix. Only the Stem Form has changed, so the change in translation is caused entirely by the choice of Stem Form.

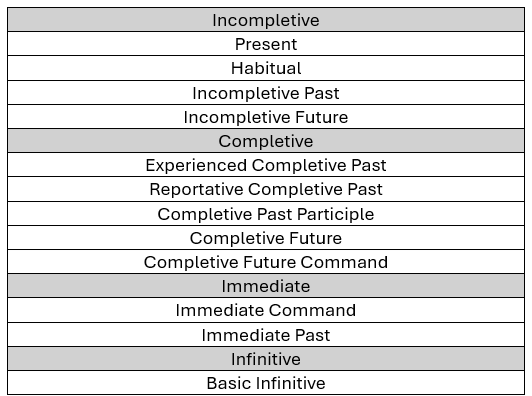

You should think of Stem Form as preceding Verb Tense—Stem Forms are a “foundation” upon which Verb Tenses are built. Every Cherokee Verb Tense can be categorized based on which Stem Form it attaches to—or which Stem Form it “occurs within,” whichever way of saying it makes the most sense to you. Here’s a (non-exhaustive) table to help you visualize it:

From here, we’ll focus on each Stem Form category one at a time, explaining how each Stem Form type contextualizes verb actions differently.

The Incompletive (NCMP) Stem Form.

For reasons that will be described below, I treat this category as including the Present Continuous Stem Form. I do not consider them to be separate. Instead, I see the PRC as a subcategory of the NCMP. But I’ll explain that more in detail below. For now, let’s focus on how NCMP Stem Forms contextualize a verb action.

Incompletive Stems describe actions as if they are still ongoing. This is one of the reasons the Present Tense can (and should, in my opinion) be thought of as Incompletive—Present Tense actions are currently ongoing, inherently incomplete.

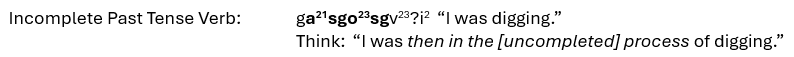

Remember: the distinction is based on how the verb is framed, not based on the reality of the action itself. So the NCMP Stem can be used to describe past actions that are, in fact, completed. The following verb describes a past action that is done, but describes it as it was ongoing in the past.

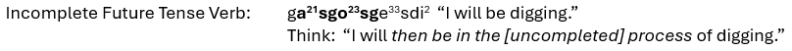

The NCMP Stem can also be used for actions that haven’t begun yet, or haven’t happened at all—i.e., Future Tenses:

So keep in mind: an action does not have to be actually ongoing for you to use an NCMP Stem. Stem Forms are chosen based on how you want the action to be imagined in the specific context of what you are saying—how you want to frame the action. If you are framing the action as an ongoing, “in-process” activity, you’ll probably need to use an NCMP Stem.

Here’s another way to think of it: NCMP Stems emphasize the action as a span of time over which the action occurs, occurred, or will occur—as opposed to emphasizing a specific singular occurrence of the action (which would be more characteristic of the CMP Stem Form). For this reason, the NCMP Past forms are often used in a “narrative” kind of way. Note how, in the following examples, the NCMP Past forms are used to describe one action as a span of time during which another event occurred—this is why the English translation includes the word “while,” even though there is no single Cherokee word in the original that equates to it:

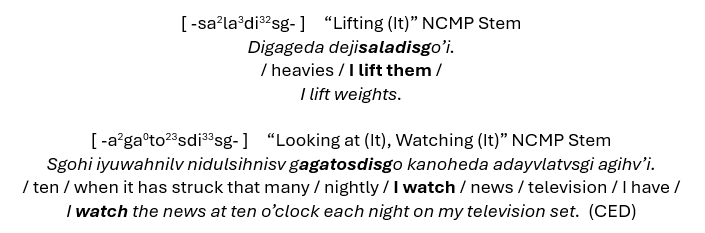

The NCMP Stem Form is also used with the Habitual Tense Suffix /o33?i2/ to form the Habitual Tense. The Habitual Tense is for actions that happen “habitually,” regularly, without referring to any one specific instance of the action taking place. This Tense only occurs on NCMP Stems because it describes patterns of behavior that are ongoing. Note how both these examples describe recurring activities—habits:

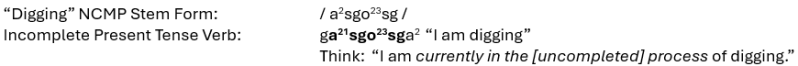

The NCMP Stem Form is frequently seen with the Motion Focus Root Suffix /h/ or the Subject-Object Root Suffix /sg/. Because of the “in-process” character of NCMP forms, emphasizing the motion of the action with /h/ makes sense intuitively. The /h/ Root Suffix is especially common in the Present Continuous subcategory of NCMP Stems—in those cases, it’s very common for the Root Suffix to Shift to Subject-Object /sg/ in non-present tense NCMP Stem uses. The Subject-Object Root Suffix’s relationship to NCMP forms is a bit less intuitive—my best guess is that there’s something about the “cause-and-effect” element of an action that is considered somehow inherently dynamic or in motion to Kituwah thought, and that dynamic quality is associated with the in-progress aspect of Incompletive Ideas.

Let’s use that last example to segway into the next subtopic—the relationship between the Present Continuous and Incompletive Stem Forms:

Relationship Between Present Continuous (PRC) and Incompletive (NCMP) Stem Forms. Historically, these have been treated as two separate Stem Forms, and there’s a reason for it: many verbs do use distinct Stem Forms (i.e., different Root Suffixes) from the Present Tense to other NCMP tenses like the Habitual. Despite this, it is more accurate overall (and less confusing pedagogically) to classify the PRC as a subcategory of the NCMP—for two main reasons:

First, the actual grammatical reason: many verbs do not have distinct Stem Forms from the PRC to the NCMP. For many, many verbs, the PRC and the NCMP are literally indistinguishable as separate Stem Forms.

Second, the purely pedagogical reason: Present Continuous verbs describe actions that are ongoing right now—meaning they are inherently “Incomplete.” Because Present Continuous actions are incomplete, it just makes sense to include them within the category called “Incompletive,” is what I’m getting at.

When verbs have distinct PRC and NCMP forms, the most common pattern is for the PRC form to use the Motion Focus /h/ Root Suffix, while other NCMP forms switch to the Subject-Object Focus /sg/. This makes sense, if you remember that Root Suffixes serve primarily to shift the emphasis of the verb from one thing to another.

Because Present Continuous forms are talking about something actively happening right here and now, it makes sense that they tend to emphasize the motion of the action. You could also think of this as emphasizing the active occurrence of action as the focus, which makes sense because of the immediacy—the “right-here-and-now-ness” of the action.

But when an action shifts out of the PRC tense, to other Incompletive uses like the NCMP Past or the Habitual, the immediacy of the action is less important—instead, the focus frequently shifts to the action’s cause-and-effect quality. Hence, the shift to the Subject-Object /sg/ Root Suffix.

So in verbs that follow this pattern, you can think of it like this: while the action is actively ongoing, the action itself is considered more important, so Motion Focus /h/ occurs. If the action is not actively ongoing in the present, the consequences of the action are more emphasized than the action itself, so the Subject-Object Focus /sg/ occurs.

The Completive (CMP) Stem Form.

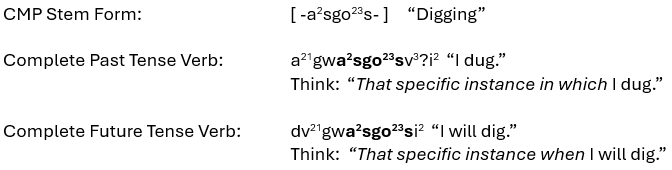

The CMP Stem Form, and Tenses built on it, emphasize actions as occurrences. It emphasizes a moment in which a particular instance of the action takes place. It doesn’t matter whether the action is actually completed or has actually occurred. CMP Stems can be used for Future Tenses or hypotheticals, both of which are actions that are not “completed.” Just like the NCMP Stem, the CMP Stem is a matter of how a speaker chooses to frame an action. If you are describing the action as a moment or an incident—as opposed to describing it as a span of time—you’ll want a CMP Stem form.

To better illustrate this “moment” meaning—and how it interacts with NCMP forms—let’s return to some earlier examples:

You should note this important point. Often, the contextual interrelationship between two verbs—and the specific Stem Forms and Tenses they take—clarifies much of the intended meaning of a sentence. When a teacher tells you that something is understood or clarified “by context,” this is often what they mean. There is a logical relationship between the verbs understood by Cherokee thought processes, and that context provides much of the same information we get from helping words and prepositional phrases in English. Note how, in the above examples, there is no Cherokee word that directly equates to “while,” for example—that’s why I put it in [brackets]. Little words like that are generally not necessary in most Cherokee sentences, because the way the verbs are framed usually makes them unnecessary.

The “while” is implied by the existence of an NCMP Verb—which presents one action as a timeframe—followed by a CMP Verb, which presents another action as a moment. The fact that the CMP moment falls within the NCMP timeframe—i..e, it happened while the NCMP verb was ongoing—is understood intuitively.

Your brain is hardwired for English, so these kinds of assumptive “leaps” will feel extremely unintuitive at first. Your brain will resist assuming the existence of information you would usually receive from helping words. Just be aware of this unique challenge and work to overcome it—it’s not as hard as it seems. You just need to understand the logic of Cherokee and work on internalizing it for yourself, which you can begin doing by challenging your own English-speaking assumptions about language and the nature of so-called “common sense” itself.

One thing you can do is pay attention to the things you say when you speak or hear English—how much can you cut out of an English sentence before the meaning is totally lost? It’s probably more than you think. If you can cut something without losing meaning, ask yourself: Why was the word used in the first place, if it was ultimately unnecessary? What did the word do for the sentence? Why were you able to understand the sentence without it?

As far as the “common Root Suffixes” go, the situation with CMP Stems is pretty simple (at least compared to NCMP Stems). JW calls the Root Suffixes most associated with CMP Stems “Completive Focus Root Suffixes,” because there’s a one-to-one relationship between the emphasis created by the Root Suffix and the completive character of the Stem Form. Whereas the dynamic qualities of NCMP Stems require you to think about more abstract ideas like “motion-focus” or “subject-object focus,” Completive Focus Root Suffixes emphasize the completive character of the action as-described. The only downside to the Completive Focus Root Suffixes is that there isn’t just one.

Note: That last one I just mentioned—/hn/—is not exactly a “true” Root Suffix. Instead, it is a shortened form of /a2hn/, which JW calls the “Populative Infix.” It is used to make Completive Stem Forms of verbs containing “incorporated Infinitives,” and is also often seen on “Particle-Based” verbs. You don’t need to know what either of those things mean quite yet—you’ll get there—I just wanted to be sure and note it now so it doesn’t lead to confusion later. At this point in your learning journey, you just learn to associate sounds like /hn/, /ahn/, /tan/, and /stan/ with CMP Stem Forms.

The Subject Focus /s/ Root Suffix is also used to make many, many CMP Stem Forms—honestly, in my experience it seems even more common in CMP Stem Forms than the actual CMP Focus Root Suffixes. It is especially common on the CMP Stem Forms of verbs that use the Subject-Object Focus /sg/ in the NCMP Stem—so if you see /sg/ in the NCMP, there’s a good chance it’ll shift to /s/ in the CMP.

JW tells me the Subject Focus /s/ can be thought of as either: 1) emphasizing the actual grammatical Subject of the action (the person doing the action); or 2) emphasizing the occurrence or existence of the action as the subject of conversation (emphasizing the action’s occurrence as the topic being discussed). Especially in the latter sense—the occurrence of the action as a topic—the /s/ Root Suffixes relationship to the CMP Stem makes a lot of sense. If the CMP Stem Form frames actions as moments, the Root Suffix emphasizing the action as an occurrence fits like a glove.

The Immediate (IMM) Stem Form.

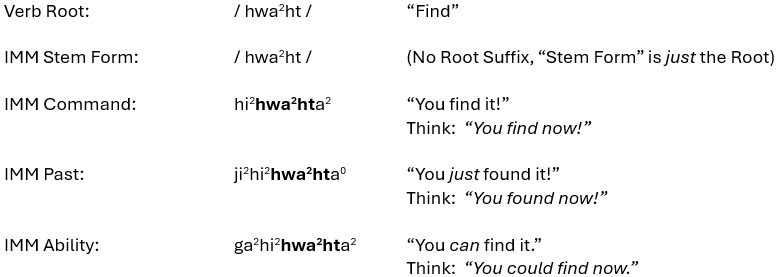

This Stem Form is unique—the IMM Stem of some verbs actually uses no Root Suffix at all! I think there’s an easy way to understand this: the IMM Stem Form emphasizes nothing but the raw character of the action itself, it emphasizes only that the action exists. You can think of it as almost a knee-jerk reflexive reaction to the occurrence of an action. If you are in a crowded building and you see flames, you don’t say “I see now that something is burning inside this building,” or “I see a fire right now” or even “I see fire!” You cut straight to the point—“fire!”

JW Webster observed that the IMM Stem Form is often characterized by “naked roots” that take no Root Suffix at all. In these cases, a Present Tense Suffix (/a2/ or /i2/) attaches directly to the end of the Verb Root. Without the specific emphasis provided by a Root Suffix, the resulting verb emphasizes only the existence of the action.

With this in mind, the uses of the IMM Stem should make perfect sense:

- It’s used for commands—specifically when commanding someone to do something right here and right now. This is the IMM Command Tense.

- It’s used to talk about things that just happened, within the last hour or so. This is called the IMM Past Tense.

- It’s used to talk about things that could happen, or things someone could do—right here and now, if they so chose. In other words, it’s often used to talk ability, whether someone can do something. I like to call this the “IMM Ability” usage. I say “usage” because it’s not exactly a tense—but you could almost think of it as a sort of “IMM Future” tense because it concerns things that could happen in the immediate future if someone chose to act on their ability.

Most Tense Suffixes are unusable with IMM Stem Forms. Immediate Stems are basically “locked in” to taking one of the Present Tense Suffixes—either /a2/ or /i2/. Because you can’t mix and match Tense Suffixes, distinguishing between the three main uses of the IMM Stem can be complicated. I’ll address that topic in its own writeup later—once it’s done, I’ll update this document with a clickable link to it here. For now, here are some examples to illustrate these uses:

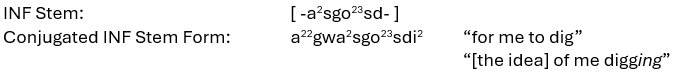

The Infinitive (INF) Stem.

The Infinitive Stem stands beside the Immediate Stem as the second “oddball” Verb Stem. The INF Stem Form frames the verb as an idea of action, rather than an actual action. It is always formed using the Infinitive Focus Root Suffix /d/ and the “State of Being” Present Tense Suffix /i2/, which I also like to call the “Timeless Infinitive Tense,” or the “Infinitive Copular Tense.” This means that, like the Immediate Stem, you do not get to pick and choose which Tense Suffixes you use on an Infinitive Stem—it’s basically always going to be /i2/, or its long form /i23?i2/.

Sometimes the Infinitive Focus Root Suffix is paired together with other Root Suffixes, making Compound Root Suffixes:

I mentioned that I like to call the /i23?i2/ the “Infinitive Copular” Tense Suffix. In linguistics, a “copula” is a word or phrase that basically equates to “is” in English—a word that refers to a thing existing in a broad sense, a thing being. In our classes together, JW Webster often translates /i23?i2/ directly to mean that a thing “is,” in a way disconnected from any specific timeframe. This is why I call the Tense Suffix “Copular”—it communicates the existence of something in a timeless way, a basic statement that something is.

Because the INF Stem is unbound from any specific timeframe, and does not describe any actual occurrence of an action, the INF Stem is understood to be inherently “Unreal.” “Reality,” as a grammatical category, is an important part of Cherokee language that deserves its own in-depth essay. For now, all you need to know is that a “Real” action is one that is or was actually happening at some point. An Unreal action is one that is not or has not happened—so negative verbs, hypothetical statements, future tenses, commands are all Unreal. Infinitive forms are especially Unreal because they are actions as ideas, as concepts.

Infinitive Stem Forms are used in a number of different ways. I’ll take a moment here to briefly introduce you to the most common and important INF Form uses:

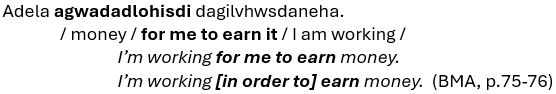

“Infinitive Complement” or “Object Infinitive.” Cherokee INF Stem Forms are loosely analogous to two English verb forms: 1) the English Infinitive (“to [verb]”), and 2) the English gerund (“[verb]ing”). In English, both verb forms are used to nominalize (i.e., “make-noun-like”) verb actions—to talk about verb actions as if they were things. This means you can use the INF Form of a verb as the focus or object of another verb. Like this:

“Adverbial Infinitive,” or “Explanatory Infinitive.” This is when an INF Form is used to provide an explanation for the action described by another verb:

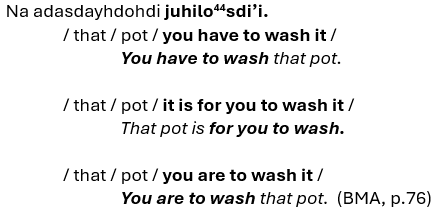

“Obligatory Infinitive.” This is when an INF Form is used to express an obligation—that a person “must” or “has to” do another action. This form requires a tone shift—a “super-high” / 44 / tone placed on the rightmost long vowel in the INF verb. I’ll provide a few distinct glosses to help you get a feel for the “obligatory” meaning:

“Ability Infinitive.” This is when an INF Form is used to express a person’s ability to do a verb’s action—or to refer to a person’s unique inner capacity for an action. This use also requires the superhigh / 44 / tone shift on the rightmost long vowel, like the Obligatory Infinitive. It is commonly seen with helping words like /eli/ or /eligwu/, which mean “able,” or a special set of “fused” Pronomials—“fused” with the Ability Prepronomial / ga2 /, that is—which are used for the purpose of expressing Ability:

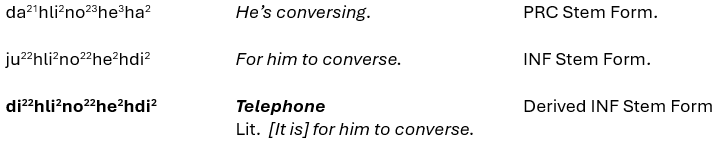

Infinitive Derivations. Finally, INF Forms are used a lot to create nouns. The process of creating nouns (or any other kind of word, for that matter) out of a verb is called “Derivation.” Derivation is a big, big subject in Cherokee language and is best left for later. For now, just note that INF Verb Stems are very commonly used to create Cherokee Nouns, and that the process looks like this:

Note: Noun derivation is not exclusive to INF Stem Forms—NCMP and CMP Stem Forms may be used to derive nouns as well. But INF Stem derivation is prevalent enough that it’s safe to see the INF Stem as having a kind of “special” relationship with derivation as a process.

CONCLUSION

The terms “Present Continuous,” “Incompletive,” “Completive,” “Immediate,” and “Infinitive” refer to “Stem Forms” in which any given Cherokee verb may exist. Stem Forms provide the foundation of Cherokee verb tenses by framing the action of a verb in distinct ways, and are usually distinguished from one another by changes in Root Suffix. The distinct framing created by each Stem Form is summarized in the following table:

Study Tips. Let’s tie all this together with some concrete advice on how to work this information into your studying. In my experience, it has been extremely difficult to study Cherokee verbs as vocabulary words. Acquiring new vocabulary is one of the least glamorous parts of learning any language. It’s the grinding, monotonous, rote memorization part, and there’s just no way around it. In most other languages, it’s really easy to memorize new words by slapping them onto a flash card and quizzing yourself. But Polysynthetic Cherokee words (especially Cherokee verbs) change so dramatically from one example to another that it can be difficult to figure out where to start—what are you supposed to put on the flash card? If you just use one form—like the Index Form in the CED—you’ll get really good at recognizing the Singular Third Person Present Tense form of the verb, and that’s it. You could expand to include all of the Index Forms, but you’ll just have a slightly better version of the same problem.

The solution is to memorize these words in pieces. You want to learn the most modular word forms you can, the forms of the word that you can copy/paste into different situations by stitching new Pronomials or Tense Suffixes directly onto it. In my opinion, this means you should start with Stem Forms. Here’s the specific approach I suggest:

First: Isolate Stem Forms and study them like vocabulary words. For any given verb you want to learn, isolate each distinct Stem Form you see among the Index Forms in the CED. This will be the Index Forms minus Pronomials and Tense Suffixes. Study each Stem Form as its own vocabulary word—each one gets its own flash card, for example. Label them according to the dictionary meaning provided for the verb and which Stem Form each entry represents. For distinct PRC Stems, IMM Stems, and INF Stems, include the Tense Suffixes because they don’t change. Take a look at the “How to Use” document on my Verb Tables page to see how I categorize and label different Stem Forms—that might give you a good place to start. For example, here’s how I studied the Stem Forms of the verb for “Wanting,” each line representing its own separate card:

Second: Once you have the Stem Forms memorized, make new cards showing fully conjugated “Index” verbs in different Persons and Tenses. At first, focus only on the most common Pronomials—1st, 2nd, and 3rd Person Singulars (“I,” “You,” and “He/She/It”) in as many different Tenses as you can. Don’t try to learn every possible conjugation all at once. Be efficient—before you make cards, try to imagine the contexts in which you are most likely to use the verb, the forms you are most likely to need, and focus on those specific conjugations first. This process will help you internalize fully-conjugated, usable forms of the verb. It’ll also help you get comfortable recognizing the verb as a Stem Form embedded in other information, help you learn to recognize the verb even when sandwiched between Pronomial and Tense Suffix morphemes. For help focusing on the most useful conjugations, you can take a look at how I categorize verbs based on “transitivity type” in the “How To Use” Verb Tables document—it may be helpful to you.

Third: Once you’ve got a grasp of Index Forms of a given verb, shift to studying by reviewing the verb in the context of complete sentences. Move away from flash card-style study and towards reading, writing, and speaking. Write as many sentences as you can using the verb, in as many different contexts as you can imagine. If possible, review the sentences you write with your instructors or other students. Try and think of actual situations where you can use the verb, and try using the verb in conversation with a speaker whenever you get the opportunity—and when you do, ask for feedback. “Did I use that word right?” “When I said [x], how did you understand it?” “Here’s what I was wanting to say when I said [x], did I do it correctly?” That kind of thing.

Finally, once you firmly know a verb and feel comfortable using it—don’t say it in English ever again unless you have to. Even if you don’t have other Cherokee speakers to talk to, you can always practice talking to yourself and thinking in the language. As you practice talking to yourself, new questions will occur to you—you’ll hit snags where you aren’t sure how to say something you want to say. Write that down and review it with your teachers, speakers you know, or other students as soon as you can.

I believe starting with the Stem Forms is the best way to structure this learning process—because the Stem Forms are the easiest way to produce easily study-able, “flash-card-friendly” forms of the verb that are useful for speech, and because it is easy to build on Stem Forms as a foundation.

If you study only the Verb Roots, you’ll acquire no useful vocabulary outside of the morphemes themselves—you won’t know which Root Suffixes to use in order to form the different Stems. If you study only fully conjugated “Index Forms” at first, you may struggle to remember where the Root begins or ends, whether it begins with a vowel or not, etc. If you study only the Index Forms provided by the CED, you may also struggle to remember certain details like: the NCMP Past doesn’t have to use Set B (because the only Past Tense Index form in the CED is the CMP Past, which uses Set B), or that only CMP Past Tenses shift to Set B (because the only CMP Stem Forms shown in the CED is a Past Tense which shifts to Set B), or that you can use Set B Pronomials on so-called “Set A” verbs even outside of CMP Past Tenses (because the CED only shows Set A on most Present Tense Index Forms for “Set A” verbs), and so on.

Anyways, that’s all for now. Good luck!

By: J.R. Lancaster, a second language learner. May contain mistakes.

Add comment

Comments