Introduction to Pronomial Prefixes: Cherokee Pronouns

“Pronouns” are words used as “stand-ins” for other words, especially Nouns. Consider the following sentence:

Doesn’t that sound strange? Once the idea of something has been introduced, Pronouns let you avoid the repetitive awkwardness of referring to the thing by name over and over again, like this:

The Cherokee language has its own form of Pronouns—the Pronomial Prefixes. Pronomial Prefixes have been—for me, at least—one of the most challenging things about learning Cherokee language. So brace yourself, this is a big topic.

We’re going to start off as simply as possible, by first discussing English Pronouns and how they work. This will help you establish a baseline understanding of Pronouns, Grammatical Person, and a familiarity with how you are accustomed to using and understanding your own language’s Pronouns. Then we will turn to Cherokee Pronomials, and discuss their most important qualities by way of comparison to English Pronouns.

The Usual Disclaimer, but more Emphatic Here: The topic of Pronomials, how they work, how to use them, is one I’ve struggled with a lot in my language learning process. I suspect this may be a common pain point for English-speaking learners. Pronomials are a big topic and they’re really hard to get used to, at least if you’re anything like me. So, as with all my writing on Cherokee language, please keep in mind that I’m a second language learner and I may get some things wrong.

One Extra Disclaimer: Because Pronomials are a big topic, and one that I find really challenging, I have written and re-written this Essay like five times by now and I can’t seem to find a version of it that I’m really happy with. I want to be done with it and move on, so I’m calling it finished and putting it out in its current form. I feel like it could use some rewrites, particularly to reorganize the information. If the essay seems a bit jumbled together or poorly organized—I agree, and I apologize. It’s the best I can do for now.

Pronouns, Grammatical Person, and English Pronouns

In basically every language that has them, Pronouns are closely tied to the idea of “Grammatical Person.” We need to unpack that idea before we move on, or else you might get tangled up in some strange-sounding terminology.

“Grammatical Person” is how languages distinguish grammatically between different people or things that may be discussed. The different kinds of “Person” are distinguished based on the “Person’s” relationship to the conversation. A Person who says something (including you whenever you are speaking) is a “First Person.” The person spoken to, the “listener” is a “Second Person.” Others, who are either not present or are being spoken about without being spoken to are “Third Persons.”

In English, the First Person is denoted by the Pronoun “I.” Second Person is “you.” Third Person is “he,” “she,” “it,” or “they.”

The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Person distinction is—as far as I know—basically universal to human languages. I’ve never heard of or studied a language that didn’t divide Grammatical Person according to exactly these three Categories. Beyond 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Persons, however—languages begin to differ dramatically from one another based on how they further categorize the distinct Grammatical Persons that can exist. We’re going to begin by discussing the Grammatical Qualities used in English Personal Pronouns.

First is the quality of number—Plurality. A single Grammatical Person can refer to one actual thing or human, or it can refer to multiple things or people. In English, we only have two categories of Plurality—Singular and Plural. So in English, for example, we have a 1st Person Singular “I,” as opposed to a 1st Person Plural “We.” “You” as opposed to “y’all.” “He” as opposed to “they.”

Next is the quality of Grammatical Gender—English doesn’t do a lot with gender, grammatically speaking, but I’m sure you’re at least a little familiar with the Grammatical Gender systems of languages like Spanish or French. In those languages, pretty much every Noun gets categorized as either “Masculine” or “Feminine,” and words referring to those Nouns have to be inflected to agree with the Noun’s gender. Like I said, English doesn’t make a big deal out of Grammatical Gender, generally speaking—we don’t have Masculine or Feminine Nouns like Spanish. We do, however, have distinctly Gendered Pronouns for our Singular Third Person Pronouns. The difference between “he,” “she,” and “it” is entirely a Gender issue. Other English Pronouns—1st Person, 2nd Person, and 3rd Person plural—do not change based on Gender. Both men and women call themselves “I,” with no distinction—and you are referred to as “you” regardless of your gender. It’s only the 3rd Person Singulars that change based on gender.

The last quality we’ll is the Subject/Object distinction. In English, the Pronouns used for most Grammatical Person categories change based on whether the Pronoun is serving as the Subject or the Object of a verb. The “Subject” of a verb is the Person performing the action. The “Object” of a verb is the Person receiving the action.

So, if I am the one acting, I use the 1st Person Subject Pronoun “I.” For example, “I see John.” But if I am the one being acted on, I use the 1st Person Object Pronoun “me.” For example, “John sees me.” The Second Person does not make this distinction at all—we use “you” regardless of whether “you” refers to a Subject or an Object.

The following table lays out the English Subject/Object Personal Pronouns, accounting for all the distinct categories we’ve mentioned so far:

There are more English pronouns—Possessive Pronouns like “mine” and “his,” Reflexive Pronouns like “yourself,” “herself,” and “themselves.” Words like “where,” “what,” and “which” can function as Pronouns in certain contexts—but we’re focused on the absolute basics of English Personal Pronouns for the time being. English Pronouns and how they relate to Grammatical Person on the simplest level. The above table of Subject/Object Personal Pronouns is meant to be just enough to give you a basic idea of how things work in English. This will help you establish a “base-line” for the Pronouns that you’re used to in your own language, and give us a familiar point of comparison when we start talking about Cherokee Pronomials.

Don’t get confused by the way we talk about this topic! Think of each distinct square on that table as denoting precisely one Grammatical Person. You may see “Person” with a capital “P,” in its singular form—even when referring to things that are plural. For example, “the 1st Person Plural Object, Us” is a single Grammatical Person, even though “us” is plural. When you see “Person” with a capital “P,” it is referring to the grammatical topic of Person, not any one human being. So yes, “we” is a plural word, but it represents one Grammatical Person, the 1st Person Plural Subject.

So let’s quickly review the main points of English Personal Pronouns:

- English Personal Pronouns are stand-alone words that refer to Grammatical Persons.

- English, like nearly all languages, divides Grammatical Persons into 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Person categories.

- English grammar only has two number categories—Singular and Plural.

- English 3rd Person Singular Pronouns differ based on Gender.

- English Personal Pronouns differ based on whether the Pronoun is serving as the Subject or the Object of a verb.

With that out of the way, let’s turn to the real topic: Cherokee Pronomial Prefixes.

Cherokee Pronomials are Prefix Morphemes—not words.

Cherokee Pronomials cannot stand on their own as words. They must be attached to another word’s root in order to be used, but that goes both ways. Pronomials are unintelligible unless they come attach to another word’s root, but most word roots are also unintelligible until a Pronomial is attached to them. This is true of verbs, adjectives, and (most) nouns. So nearly all Cherokee words require a Pronomial before they can really be considered a complete “word.

Pronomials attach to the beginning of word roots—so they come before the root. So they are “Prefixes”—hence the name, “Pronomial Prefix.” They don’t always come at the very beginning of a fully formed word, though, because there is a category of Morphemes called “Prepronomial Prefixes” that, unsurprisingly, come before Pronomials. But those are a topic for another time. For now, just note that Pronomials come before the word root, so you can usually find them near the beginning of a fully formed word.

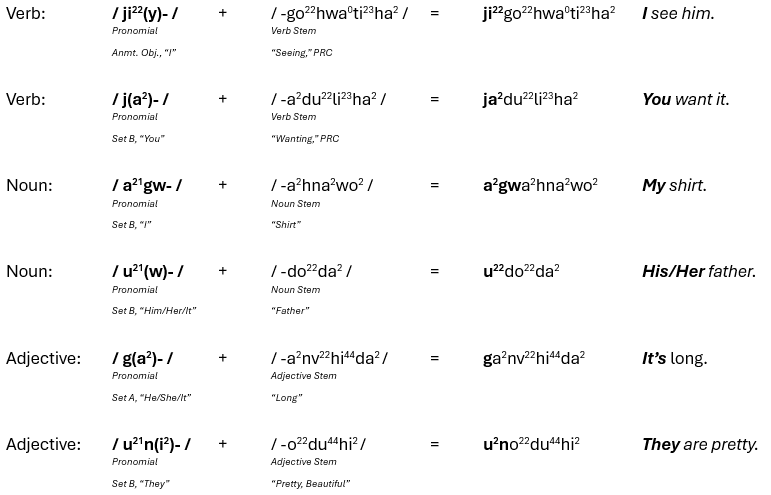

The function of Pronomial Prefixes changes somewhat based on the kind of word to which it attaches. They can express Subject/Object information when attached to verbs, possession when attached to certain categories of Nouns, or denote the “subject” of an adjective (i.e., specify the Person described by the adjective). Here are some examples:

Although I just finished describing how Pronomials function “differently” based on the word-type to which they attach, I’d caution you against really thinking about it like that. The deeper you get into Pronomial Prefixes, the more you’ll realize that they really aren’t “functioning differently” from one word type to another—it’s just that we have to treat them differently from one word type to another for the purpose of translation into English.

So—unlike Enligsh Personal Pronouns, which stand on their own as words like “he,” “she,” or “we”—Cherokee Pronomials are Prefixes that must be attached to the roots of other words in order to be used. And almost every complete Cherokee word includes a Pronomial somewhere near its beginning—because most word roots require Pronomial inflection in order to be understood as complete words.

Cherokee Pronomials also denote Person, but every Pronomial denotes two distinct Persons—Subject and Object.

Each single Cherokee Pronomial explicitly denotes a specific Subject-Object relationship—which is to say, every Cherokee Pronomial denotes a specific relationship between two distinct Persons.

In English, Pronouns distinguish Subject and Object by taking specific Subject/Object forms. Beyond that, English verbs denote Subject/Object relationships with a strict word order rule of Subject-Verb-Object—“cat bites dog,” or “she bit him.” Cherokee, by comparison, wraps all this grammatical information into one single tool—the Pronomial Prefix.

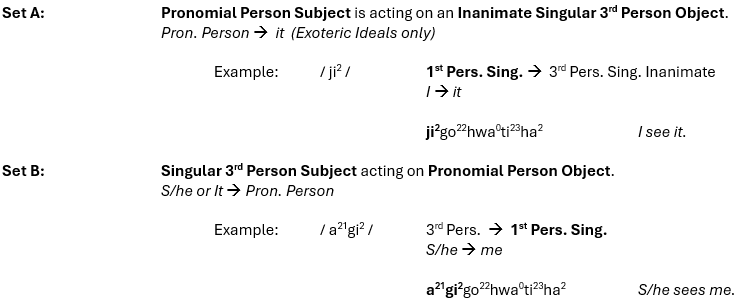

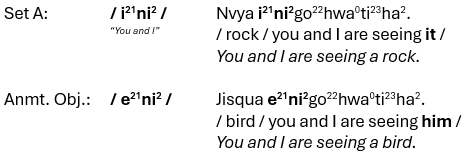

Pronomials have historically been divided into “Sets” based on what Subject/Object dynamic they depict. In all these examples, the “Pronomial Person” is the specific Person most explicitly denoted by the Pronomial.

There is one major wrinkle to this Subject/Object system in Cherokee Pronomials that took me a long time to understand, and it concerns Set A and Set B. I elaborate on this topic much more—maybe too much, honestly—in another essay that I’ll link here when it’s finished. For now, I’ll summarize it like this:

I know this is a lot to throw at you, and this probably isn’t the best place to introduce this particular topic. But, I wanted to tackle it here, at least on a surface level—because I have to assume you’re using the CED in your learning process. You may have noticed that many verb entries show a verb using Set B /u21(w)/ instead of Set A /a21/ in the Past Tense form ending in /v23?i2/.

This brings us to a related topic: so-called “Set A Verbs” and “Set B Verbs.” You’ll definitely hear these terms in your study, so let’s unpack them now:

If a verb can use Set A in the Present Tense, it’s considered a “Set A” verb and its main Index Form will be listed in the CED with the Set A Pronomial /a21/ attached. Set A verbs can use Set A or Set B in basically every Tense, unambiguously—except for CMP Past Tenses and Infinitive Forms. In those forms, Set A becomes ungrammatical, and Set B becomes ambiguous. If a verb cannot use Set A in the Present Tense, it’s considered a “Set B” verb and it’ll be listed in the CED with the Set B Pronomial /u21/ attached. Set B verbs can never use Set A Pronomials and Set B Pronomials attached to them are always ambiguous no matter what tense you use.

Now that we’ve opened that can of worms, let’s close it back up and move on to simpler things:

Cherokee Pronomials do not denote gender.

“Gender” does not exist as a Grammatical Category anywhere in the Cherokee language. Don’t misunderstand me—of course Cherokee language still has “gendered” words like “man,” “woman,” “boy,” or “girl.” I’m not saying it’s impossible to talk about or distinguish gender in the Cherokee language. But you will never have to take gender into account while conjugating a word. You don’t have to do things like picking between /o/ or /a/ endings to mark things as Masculine or Feminine like in Spanish. You don’t even have to distinguish between “she” and “he” when picking Pronomials.

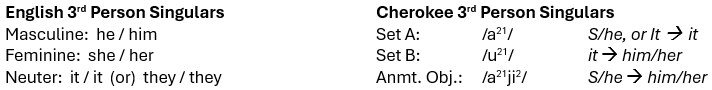

Remember, the gender distinction only matters in English when we’re talking about 3rd Person Singular Pronouns—so let’s compare them to Cherokee 3rd Person Singular Pronomials.

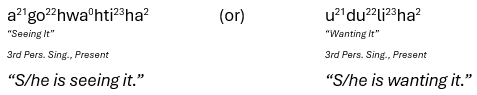

So, when you see a verb conjugated with a 3rd Person Singular Pronomial, like:

You have absolutely no way of knowing—without more context—whether the Pronomial is referring to a man or a woman. So you’ll notice that each of the examples listed are translated with a “she or he” (which I prefer to write as “s/he”) or “him/her” meaning. But you may have also noticed that the translations seem to change from “s/he” or “him/her” to “it.” That’s because:

Cherokee Pronomials explicitly denote the “Animacy” of the Object Person.

Cherokee Pronomials do not reflect Grammatical Gender, but they do reflect Grammatical Animacy. This will feel new and strange to you, because English doesn’t treat Animacy as a distinct Grammatical Category—our grammar doesn’t change based on whether we’re talking about living or nonliving things. But in Cherokee grammar, Animacy is about as important as Gender is in Spanish or French—you need to pay close attention to it.

Animacy’s biggest impact on grammar is usually reflected in which Pronomial Set you use on a verb where the Pronomial Person is the one acting. If the Pronomial Person is acting on an Inanimate Object, use Set A. If the Pronomial Person is acting on an Animate Object, use an Animate Object Pronoun.

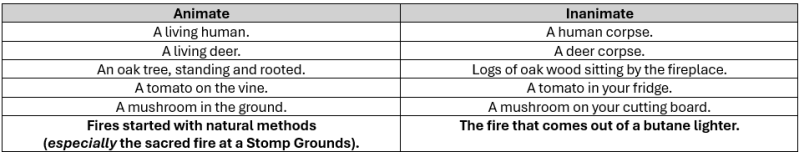

Anything you know to be actually living will be considered “Animate” for the purposes of grammar—humans, animals, fungi, plants, and so on. Once a living thing dies, its body is spoken of as Grammatically Inanimate. So, dead bodies, felled trees, cut grass, and so on—all these are Inanimate. Fruits and vegetables, once cut from the plant from which thew grew, are also Inanimate. Generally you won’t have to think very hard about whether to talk about something as Animate or Inanimate. Here’s a table of comparable examples:

Important Note: There’s apparently a bit of flexibility in what is or is not considered Grammatically Animate, and different speakers may apply the standards differently. For example, I once read that some speakers treat fruits and vegetables as animate even after they’re harvested—I’ve never heard anyone speak of harvested fruits or vegetables as animate in my own experience, but apparently there is some variance among speakers there. It’s just something to keep in mind!

The Animacy Distinction is primarily concerned with the Object of an action. This Animacy distinction is very important in Cherokee grammar, but don’t feel overwhelmed—you only have to worry about one thing, the Animacy of the Object, the thing being acted on. The Animacy distinction in Pronomials is based completely on the Animacy of the thing receiving the action, and the Animacy of the Subject is not usually Grammatically relevant. This can be understood with two explanations:

- Inanimate things don’t do things very often because, well, they aren’t alive. The Subject of an action is almost always Animate, because Animate things are usually the only things that can perform actions. Inanimate things are only the Subject of an action when we are speaking figuratively. The Animacy of an action’s Subject doesn’t usually need to be explicitly indicated, because the Subject can usually be presumed to be Animate.

- It’s a respect-for-life thing: an action that only affects an Inanimate Object is very different from an action that affects a Living Being—spitting on a rock as opposed to spitting on a person, for example.

So as far as Grammatical Animacy goes, you only have to worry about the Animacy of the thing affected by the action, the Object of the verb. If it’s not alive, use Set A—unless Set A is unusable (for reasons discussed above), in which case use Set B. If the Object of the action alive, use Animate Object Pronomials.

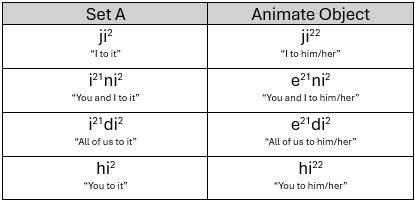

One Final Note: Set A and Animate Object Pronomials look very similar. Here are a few examples:

Do not be fooled by the similarities—these are completely different Pronomial Sets. Most importantly, this means Animate Object Pronomials do not follow the same rules as Set A. Remember when I said that Set A Pronomials can’t be used on CMP Past Tenses or Infinitive Forms, and Set A verbs have to shift to Set B in those circumstances? That rule does not apply to Animate Object Pronomials.

So don’t get tripped up on the way Animate Object Pronomials look like Set A—they aren’t the same and they don’t work the same way. The major takeaway is this: all those complicated rules I mentioned earlier about when to use Set A, when it shift to Set B, when Set B becomes ambiguous—all those rules are completely irrelevant to Grammatical Animacy and the Animate Object Pronouns. So if the action you’re describing has an Animate Object, you will always use an Animate Object Pronomial—it doesn’t matter whether it’s a “Set A” or “Set B” verb, and it doesn’t matter what tense you’re using.

Cherokee Pronomials and Plurality

In English, there’s only two number categories that matter grammatically: one (1, Singular), and more than one (2+, Plural). Cherokee is a little more complicated than that.

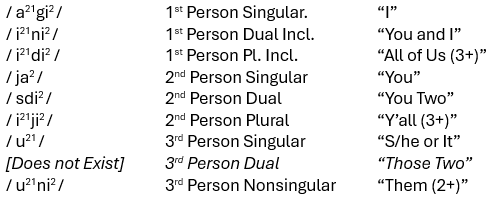

In total, Cherokee grammar distinguishes four distinct number—or “Plurality”—categories. The main three are: one (1, Singular), two (2, Dual), and three or more (3+, Plural). However, there are no 3rd Person Dual (2) Pronomials—so the fourth category only exists for 3rd Person Pronomials, and it is two or more (2+, Nonsingular).

The 1st and 2nd Persons have distinct Pronomials for Singular, Dual, and Plural forms. The 3rd Person Pronomials only distinguish between Singular and Nonsingular. Here are some examples from Set B, labelled only according to Pronomial Person (i.e., Subject/Object meaning omitted for the purpose of these examples):

There’s not much more to say about this particular quality of Cherokee Pronomials—there’s an extra category between “single” and “plural” for situations involving exactly two. But, that special “only two” category does not apply to 3rd Persons, which work similarly to English. For 3rd Persons, there’s only Singular and Nonsingular, and Nonsingular is identical to the “two or more” English idea of “Plural.”

There’s only one more quality of Cherokee Pronomials for us to cover before we’re done here:

Clusivity

Have you ever thought about the English words “we” and “us?” Have you ever noticed how ambiguous they are?

When I say “we are happy,” can you tell who I’m talking about? Probably not! “We” could mean “my wife and I,” or “you and I,” or “you and me and John,” or “all of us on earth.” This means “we” is a highly ambiguous word in English—if we wanted to rephrase that with fancy Linguistic terms, we would say “the English Plural 1st Person” is ambiguous. You have to rely on context and common sense to know exactly who is or is not included when someone says “we.”

Cherokee doesn’t work like that. There is a special Grammatical quality that applies only to 1st Person categories, and I refer to it here as “Clusivity.” Clusivity means that 1st Person Dual and Plural Pronomials distinguish between who is and is not included in Cherokee equivalents of “we”—it also means that Cherokee has four distinct Pronomials for different kinds of “we.” Technically speaking, every Cherokee Pronomial can be categorized based on Clusivity--Second Person Pronomials obviously include the listener, the 1st Person Singular and 3rd Person Pronomials obviously exclude the listener--but the distinction only really matters in First Person Dual and Plural Pronomials. So your study and your notes about Clusivity should focus on that--the different kinds of "we."

The Clusivity distinction depends on whether the listener—the person to whom you are speaking—is included or not. If the listener is included, the Pronomial is called “Inclusive.” If the listener is not included, the Pronomial is called “Exclusive.” Here are examples from Set A:

In English, all these examples would be referred to with an ambiguous “we” or “us.” A listener relies on context to clarify whether they are included in any given “we” or “us.” In Cherokee, Pronomial Clusivity makes this detail explicit.

Summary

At the beginning of this document, I used the following table to summarize the various qualities of English Personal Pronouns:

By now, you’ve probably gotten the sense that Cherokee Pronomials are much more complex than English Pronouns. To help you visualize this complexity, here’s a similar Table collating and explaining the various qualities of Set A Pronomials:

It’s a much bigger, more complicated table, isn’t it? Cherokee Pronomials carry much, much more information than English Pronouns do—they are an extremely important topic to master. And remember—this table doesn’t cover every Pronomial. It only covers Set A. There’s an equivalent table for Set B, Animate Object Pronomials, Combined Local Pronomials, and Unknown Actor Pronomials.

If this seems overwhelming, I’m sorry—it just is. Cherokee Pronomials are a huge topic and there’s a lot to learn about them. Learning this stuff can feel like drinking from a firehose. You just have to pick up the bits that you can, and know that you’ll retread this ground many times. Next time around you’ll pick something else up, then something else the next time. You’re not gonna get it all in one pass, so don’t sweat it if you can’t retain everything that was crammed into this essay after one go-over.

Review

Here’s a bulleted list of memorable main points to get you started:

- Cherokee Pronomials are like English Pronouns, but they attach to the beginning of a word root as a Prefix instead of standing alone as words.

- Almost every Cherokee word requires a Pronomial before it is intelligible as a word.

- Pronomials attach to almost every different kind of word in Cherokee--verbs, adjectives, nouns, etc.

- Cherokee Pronouns can be divided into 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Persons. 1st Persons are Persons that refer to or include the Speaker. 2nd Persons are Persons that refer to or include the Listener. 3rd Persons are Persons either not present for or not included in the conversation.

- Every Cherokee Pronomial indicates a specific Subject-Object relationship, and Pronomials are divided into “Sets” based on what kinds of Subject-Object pairing they denote.

- There is no gender to Cherokee pronouns—“he,” “she,” and “it” are treated the same.

- Cherokee Pronomials do distinguish based on Animacy—specifically, whether the Object denoted is Animate or Inanimate.

- In terms of “Plurality,” Cherokee pronouns are either Singular (1), Dual (2), Plural (3+), or Nonsingular (2+)—but the Nonsingular only shows up in 3rd Persons.

- In terms of “Clusivity,” 1st Person Cherokee pronouns either include the listener (Inclusive) or exclude the listener (Exclusive). The most important consequence of this is that Cherokee has four distinct versions of “we.”

By: Jakob R. Lancaster, a second language learner. May contain mistakes.

Add comment

Comments