Verb Idealization: Exoteric and Esoteric Ideals and Pronomial Prefixes

Disclaimer: Everything I’m about to say is based directly on the work of JW Webster. JW was the first to recognize the “shared/personal” experience distinctions between Set A and Set B verbs, and he was the first to talk about the “public/private” correlation between the Set A 3rd Person Pronomials /a21/ and /ga2/. My goal here is to gather all those ideas together in a single framework. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a way to do that without slapping a bunch of Linguistic jargon on it. After all, would it even be Linguistics without a white guy making up a bunch of obnoxious ten-dollar words for everything?

All this to say, I wrote this essay more like a Linguistic article than an instructional tool for learners--meaning it's not going to be as user-friendly as most of the other things I write. If you want to skip all the nerd-talk, you can skip to the end to find the most important learning takeaways.

I want to be sure and remind everyone, no matter how obnoxious and self-important I sound in this essay, I am not a Linguist. I have no credentials. This essay is not the product of rigorous academia—whatever that’s worth—it is just the product of me trying to make sense out of my own Cherokee language study and come up with some study-able main points in the process.

Introduction: Verb Idealization as a Concept.

Any action can be classified as “Exoteric” or “Esoteric” in the Cherokee language. This terminology is my own, but the classifications are meant to map directly onto the concepts of “Set A Verbs” and “Set B Verbs,” or what JW Webster has called “shared experiences” and “personal experiences,” respectively.

For the purposes of this writeup, I refer to this process of classifying an action as Exoteric or Esoteric as “Idealization.” In this essay I will attempt to articulate a framework for “Idealization” as a Grammatical Category in the Cherokee language. The most important consequence of Idealization relates to Pronomial Sets A and B, and how they may be used.

In Esoteric Ideals, Set A Pronomials may be used and Set B Pronomials have an unambiguous “Pronomial Person-as-Object” meaning. In Exoteric Ideals, Set A Pronomials are agrammatical (unusable), and Set B Pronomials become ambiguous as to Subject-Object meaning. Pronomial Set choice, then, must “agree” with Idealization as a Grammatical Category.

I see Exoteric Idealization as a sort-of “default” position because—in short—all the grammar rules that stem from this distinction concern how Esoteric Ideas differ from “norms” established by Exoteric Ideas.

The Idealization system is based entirely on Cherokee/Kituwah cultural perceptions of the human experience of an action. Specifically, the distinction turns on whether the action expressed is:

- perceived as one experienced in a shared way, considered basically equivalent among all people (Exoteric); or

- perceived as one experienced in a highly personal, unique way considered inaccessible to others (Esoteric).

Traditional Kituwah culture places a high premium on respecting the unique experiences and perspectives of others, so the way an action is Idealized is directly reflected in the ways people talk about it. This manifests in pragmatic matters of usage and etiquette standards, as well as in grammar itself--Esoteric actions are treated with a certain heightened reverence out of respect for the unique experiences they represent. This "setting aside" of Esoteric actions reflects the traditional attitude that people's personal experiences should be spoken of carefully to avoid improper presumption or judgment of others.

The Exoteric/Esoteric distinction is always triggered by either:

- perception of the action in the specific tense context in which it is described (i.e., all actions are always Idealized Esoterically in certain tenses); or

- perception of the inherent qualities of the action itself (i.e., some actions are always Idealized Esoterically, regardless of tense or context).

I refer to these as distinct “Idealization Processes.” I call the former “Tense-Based Idealization,” and the latter “Verb-Based Idealization.”

It is easily predictable whether Tense-Based Idealization will occur, because it’s based on the unique context imposed on a verb by a particular Tense or Form. The rules are simple: All verbs are Idealized Esoterically in all CMP Past Tenses and INF Forms.

Verb-Based Idealization is another thing entirely. Idealization is based entirely on mutable, culturally rooted perceptions of how an action is subjectively experienced, so it’s basically impossible to know whether Verb-Based Idealization will categorize a verb as inherently Esoteric just by looking at it. In other words, there is no linguistically or grammatically predictable pattern for whether Verb-Based Idealization will be applied. The only way you can know is by listening to how speakers use the verb, or by developing in yourself the Kituwah perspective necessary to intuit these categories. Inherently Esoteric verbs are basically equivalent to what have previously been called “Set B Verbs.”

Anyways, let’s get to the specific details of how the Ideal categories work and how they affect speech.

Exoteric Ideas

An “Exoteric” action is thought to be experienced more-or-less uniformly among people—it is something we all relate to more or less equally, without profound or fundamental differences in internal experience between people. I believe it is basically the “default position” of Kituwah thought to idealize most actions as Exoteric, and the grammatical and linguistic conditions surrounding Exoterically Idealized actions can be thought of as the “norm.”

It’s easy to overstate the Kituwah understanding of Exoteric actions, and equally easy to overthink them. Some philosophers would argue “Exoteric experiences”—as they’ve been framed here—are basically impossible. How can we ever know whether our experience of anything is comparable to anyone else’s? It’s like the cliché old question: how can you know what you call “red” is the same thing I see when I see “red?” Why is “seeing,” a21go22hwa0ti23ha2 Exoteric, when it seems obvious that we don’t all “see” the same way?

You may (understandably) roll your eyes at those examples—but some Exoterically Idealized actions present more concrete (less navel-gazey) challenges—“walking,” for example, is Exoteric by default. But don’t we all walk a little differently? Some people walk in long strides, some people feel extreme pain whenever they walk, some people can’t walk at all. So how can it be a shared or universal experience?

The key is to remember this: idealization is based on Kituwah cultural perceptions of how the action is experienced, and how those experiences can be effectively talked about and understood between different people. Exoteric actions, in this sense, are those actions that are uniform enough among enough people that they may be spoken of as generalized experiences. Because the experience is considered general enough, there is no need to grammatically convey the uniqueness of any given person’s experience of that action. Basically, it’s an action the experience of which is ubiquitous enough that it’s not considered generally insulting to talk of the action broadly.

No verb is Idealized Exoterically in a fundamental way—i.e., every “Exoteric Verb” must shift to Esoteric Idealization in certain Tenses. No verb is Exoteric in every context. On the other hand, certain verbs are so inherently Esoteric that they are Esoterically Idealized in all forms and tenses. There is no Cherokee verb that has the same relationship with Exoteric Idealization—no verb that must be Idealized Exoterically in all tenses and contexts.

So it begs the question—can we fairly label any verb as a “Exoteric Verb?” Or does Exoteric Idealization simply constitute a default form? In that case, Esoteric Idealization should be understood as a deviation from the Exoteric norm—said deviation based either on tense context (Tense-Based Idealization) or the Verb Root itself (Verb-Based Idealization).

I don’t think I have the brains or the patience to answer that question—but I lean towards the latter interpretation. For now, just know this: although I will be talking about “Exoteric Verbs” and “Esoteric Verbs” as two heads of the same coin, the actual relationship is more complicated than that. As long as you keep that in mind, you can generally think of “Exoteric Verbs” as synonymous with so-called “Set A Verbs,” and “Esoteric Verbs” can be treated as synonymous with so-called “Set B Verbs.”

Before we move on to Esoteric Verbs, we’re going to briefly talk about a sub-topic within Exoteric Ideas:

Public and Private Exoteric Ideas

Note (9/22/2025): This section needs revision--it may need to be excised, reworked, and reposted as its own essay altogether. In recent lessons I've had with JW, he tells me the so-called /ga/ Pronomial does not exist--at least not as a separate, distinct 3rd Person Singular Pronomial. Rather, he says there is a single Pronomial /g/ that can serve as either a 1st Person Singular or a 3rd Person Singular Pronomial. This Pronomial is totally distinct from the pre-vowel /g/ form of Set A /ji/, and exists to indicate a unique degree of familiarity with an action from the speaker's perspective. I do not fully understand what I have been taught about this yet, but it complicates the things I've written here in this section. I'm going to leave the section here for now, but I'm leaving this note and putting the whole section in italics until further notice.

Exoteric actions can be subdivided into two categories we can call “Public” and “Private.” Again, JW Webster was the first to make this distinction.

“Public” Exoteric actions are shared experiences that are so ubiquitous among people that we regularly see other people perform the action outside the home. These are actions you regularly see other people—including complete strangers—doing, especially things done by most people on a more-or-less daily basis. You don’t have to know a person very well, or at all, to witness them performing a Public Exoteric Action. “Walking,” for example.

“Private” Exoteric actions are commonly experienced actions not typically done out in public. These are the kinds of activity that most people do, but are largely confined to the home, or done away from others. An action doesn’t have to be extremely personal or private to be in this category—we’re not necessarily talking about things that would be embarassing or shameful to be seen doing.

For example, “brushing teeth” is something we all experience pretty generally, so it’s Idealized Exoterically. But at the same time, it’s not the kind of thing you’re accustomed to seeing people do out in the open. You’ve probably never seen your neighbors or your coworkers brush their teeth. The only people you’ve seen brushing their teeth are probably people you’ve lived or stayed with—so it’s a “Private” action, even if “walking in” on someone brushing their teeth probably wouldn’t be cause for any embarrassment by either person.

In the language, Public and Private Exoteric actions are only distinguished by which Set A 3rd Person Singular Pronomial they use. Public actions use /a21/, and Private actions use /g(a2)/, in 3rd Person Singular constructions.

JW Webster has argued—and I tend to agree—that these categories should be used fluidly. They should shift and change and morph with time, as certain activities become more or less public. That way, this element of the language is kept alive and productive.

For example, Kituwah people used to bathe publicly in the river every day. At that time it was normal to see other people (even strangers) out washing their hair in broad daylight, in front of everybody. You would never have been surprised to see anyone washing their hair, you might have seen someone washing their hair almost every day.

Under those circumstances, “washing hair” was a Public Exoteric activity—and that’s still how it’s presented in the CED, with /a21/ as its 3rd Person Singular Pronomial: a21li0sdu23le3ha2, “S/he is washing his/her hair.”

The CED isn’t “wrong” about this verb, but perhaps the way this verb is used should change with the times. People don’t usually wash their hair in public anymore—I’ve never seen any of my neighbors or coworkers wash their hair. If a new of the CED were published, perhaps the verb’s entry should be updated to change the Index Form to ga2li0sdu23le3ha2, “S/he is washing his/her hair.” As long as the change were noted, documented, and explained—I see no downside to this kind of modification.

I agree with JW Webster’s perspective that making these kinds of change are part of what it means to keep the language alive. If such changes are not made in authoritative reference resources that have exert a “standardizing” influence on the language—as does the CED—the distinction between /a21/ and /ga2/ could become vestigial. It could become a frozen, fossilized, dead element of the language that no longer carries any understood meaning. The expressive potential of the distinction, would be lost, and the expressive potential of the language as a whole would be diminished.

Let’s get back on track:

Esoteric Ideas

An Esoteric action is seen as fundamentally unique to the person/s experiencing it. Their experience of the action is deeply personal and internal to their mental processes, their feelings, or even their spirituality. It’s not just “Private”—an Esoteric Action is understood as totally internal to a person. We can’t ever presume to fully understand someone else’s Esoteric experience, and traditional values insist a person’s perspective on their own Esoteric experiences should be respected. For this reason, Esoterically Idealized actions cause a paradigmatic shift in the way actions are described—primarily expressed grammatically in the way Pronomials can be used.

The Exoteric/Esoteric distinction should be thought of as a “switch” that can be flipped—instead of thinking of them as two truly distinct or co-equal categories. Exoteric Idealization should be taken as the default, and under certain circumstances a “switch will flip” triggering Esoteric Idealization. The circumstances triggering this “flip” are the Idealization Processes mentioned above.

“Tense-Based” Idealization is when the switch gets flipped by the occurrence of a verb Tense that is itself understood as inherently Esoteric—either the Completive Past Tenses or Infinitive Forms. This only happens to so-called “Set A Verbs.”

“Verb-Based” Idealization is when the switch gets flipped because the verb itself is understood as inherently Esoteric from a Kituwah perspective. Such verbs are Idealized as Esoteric in all Tenses, the so-called “Set B Verbs.”

Tense-Based Idealization: CMP Past Tenses. References to specific past occurrences of an action—i.e., the CMP Past Tenses (Experienced, Reportative, and Past Participle)—are always Esoteric.

CMP Past tenses articulate actions as singular occurrences that have passed into the memories of people who witnessed or experienced them. Different people experience and internalize their own memories differently from one another. Two people can remember the same event in very different ways. I believe this is the best explanation of why CMP Past tenses are Esoteric: they refer to specific events that now dwell exclusively in the highly personal, internal world of human memory. Once a specific action is done, and that done thing passes into memory, and a speaker is referring to that remembered moment, that statement of singular memory is Idealized Esoterically to respect differences in perspective and memory. At least, that's the best explanation I can think of--I'm guessing, to be totally clear here.

NCMP Past Tenses, by comparison are not generally Esoteric, despite having similarly “passed” into memory—and this fact complicates my interpretation somewhat. I am not sure how to account for this. My best guess is that the answer lies in the character of NCMP Stems. NCMP Past Tenses lack the quality of referring to a specific instance in which an action occurred, instead framing past actions as a span of time in which the action was occurring. Perhaps NCMP Past Tenses are idealized Exoterically because they lack the singular, unique moment of action that characterizes CMP Past constructions.

Tense-Based Idealization: INF Forms. Conceptual Actions—i.e., INF Forms—are almost always Esoteric.

Infinitive forms refer to the action of a verb in an idealized, conceptual sort of way. They summon up the “idea” of the action—and each person who hears it may picture that idea a little differently.

INF Forms do not refer to any known real occurrence of the action—they “dwell in the mind” as purely hypothetical, unreal, similar to the way CMP Past Tenses “dwell in the memory.” I believe this is the reason INF Forms are Idealized Esoterically. The sole exception to this is when a Noun derived from an INF Stem is forced into Exoteric Idealization using a Set A Pronomial specifically for the purpose of signalling the occurrence of a Derivation process or the generalized character of an unpossessed, unspecific Noun.

Verb-Based Idealization: “Set B Verbs.” Some verbs are Idealized Esoterically in all tenses and contexts, based on a Kituwah perception of the action itself being highly personal and unique to a person’s internal experience regardless of tense or context.

JW Webster explains that "Set B Verbs" are those that refer to some kind of internal mental, spiritual, or highly personal process that is noted to differ from one person to another in a profound way. This includes things like “wanting,” “feeling,” “believing.”

However, it also often includes verbs describing physical sensations where peoples’ experience of the sensation is seen to vary from one person to another. For example, the weather verb u21hyv22dla2 “It’s cold outside” is an Esoteric “Set B” Verb—when one person thinks its cold, another person may feel warm!

Compare that to the Set A Verb ka2na3wo32ga2, “S/he is cold.” This verb is Exoteric, because when someone is themselves cold (as opposed to expressing the opinion that it is cold in the environment)—it is simply understood that the person is experiencing the universal feeling of what it feels like to be cold in one’s body. Because the person is expressing a shared experience, the verb is Exoteric—but if they are expressing a unique perspective, like their opinion on whether the weather outside is hot or cold, the utterance is Esoteric, because that person is experiencing the temperature in their own unique way.

Tense-Based Idealization does not apply to inherently Esoteric Verbs—they remain in the Esoteric paradigm in all Tenses and Forms, with the sole exception of generalized Nouns derived from INF Forms, which take Set A for the express purpose of flagging a shift in Idealization, which in turn is flagging the occurrence of a Derivation process so listeners understand the word is being used as a noun instead of a verb.

Table: Idealization Categories and Idealization Processes

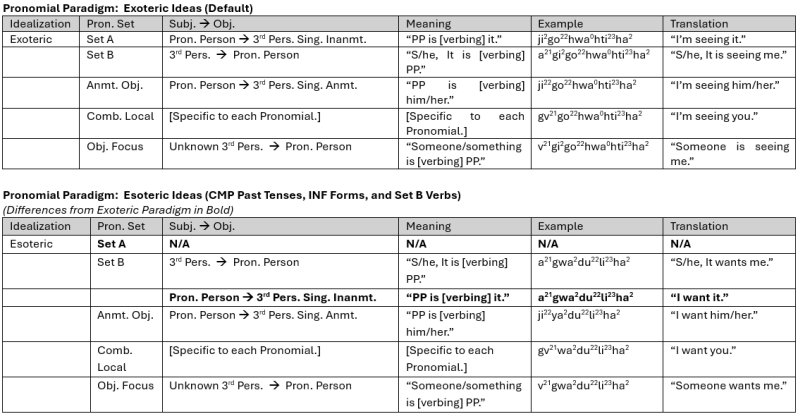

The Pronomial Paradigms

In practice, the distinction between Exoteric and Esoteric ideas is manifested in Pronomial Prefixes. There are two separate Paradigms for how Pronomials work—specifically, Set A and Set B Pronomials— from one Idealization category to another. Those Paradigms are as follows:

Conclusion: Practical Main Points for Students

What we have here is an extremely abstract Grammatical Category that (apparently) requires high-falutin ten-dollar Linguistic jargon and theorization to explain. So it sounds really scary and complicated. But here’s the good news: the practical consequences of this stuff—the things you should actually study, the takeaways most important for your actual learning process—are extremely simple.

By default, Set A Verb actions are Idealized Exoterically. This means the standard Pronomial Paradigm applies:

- Set A Pronomials can be used to denote a “Pronomial Person is [verbing] it” meaning—that the Pronomial Person is the Subject of the verb, and they are acting on a Singular Inanimate 3rd Person Object.

- Set B Pronomials can be used to denote a “S/he is [verbing] Pronomial Person” meaning—that a Singular 3rd Person is the verb’s Subject, and the Pronomial Person is the verb’s Object. In Exoteric contexts, Set B has this meaning and only this meaning—it is unambiguous.

All actions are Exoteric unless one of the Idealization Processes applies as follows:

- Completive Past Tenses always trigger a shift to Esoteric Idealization.

- Infinitive forms almost always trigger a shift to Esoteric Idealization.

- Set B Verbs are always Esoteric regardless of Tense.

When an action is Idealized Esoterically, it causes a shift in the Pronomial Paradigm as follows:

- Set A Pronomials become agrammatical. In other words, you can’t use Set A in Esoteric contexts. If you do, the resulting might be understood—but even then, it will sound strange, confusing, and/or improper.

- Set B gains the 3rd Person Inanimate Object meaning usually denoted by Set A, in addition to its ordinary “Pronomial-Person-as-Object” meaning. Because Set A is unavailable for Esoteric Ideas, Set B “picks up the slack” and takes on the role of Set A. Because Set B has two possible Subject/Object meanings in Esoteric contexts, Set B becomes ambiguous—it may need additional clarification to distinguish which Subject/Object relationship is intended.

Final Note: the Exoteric/Esoteric distinction only affects Set A and Set B. It does not affect Animate Object Pronomials, Combined Local (Person-Person) Pronomials, or Object Focus Pronomials. When using one of those Pronomial Sets, you may completely disregard the Exoteric/Esoteric distinction.

By: J.R. Lancaster, a second language learner. May contain mistakes.

Add comment

Comments