The Cherokee Verb and Its Segments

Like many Polysynthetic languages, Cherokee could be described as “verb-driven.” The verb-conjugation system of Cherokee is probably the single most complicated topic to be tackled in your learning process. Verbs are the “MVPs” of most Cherokee sentences—they tend to carry the bulk of the most important information that needs to be conveyed. A fully conjugated verb can often function as a complete sentence by itself. Beyond this, many, many ideas that are expressed in English with other kinds of words—adjectives and prepositions, especially—are expressed using verbs in Cherokee.

So make no mistake about it: verb conjugation is by far the most important, most complex, and probably the most difficult part of learning the Cherokee language for most (probably all) English-speaking students. But remember what we’ve talked about so far and stay positive. Here’s the silver lining: 1) the high importance and prevalence of verbs gives you a pretty clear roadmap for organizing your study—when in doubt, study verbs; and 2) most other topics within the language are nowhere near as complicated as verb conjugation—some topics are really easy, especially in comparison to verbs. Learning verbs is like climbing a mountain, sure, but it’s one mountain. Now that I’ve told you, you know to expect the challenge and where to focus your attention. Half the fight is already won.

In this essay, I’ll describe in very general terms the “anatomy” of a fully conjugated Cherokee verb. A complete Cherokee verb has three distinct, identifiable “segments,” and learning to recognize where those segments begin and end (especially in terms of listening) is a crucial part of comprehension. The “segment” distinctions I make here are more or less artificial—this framing of the topic is meant mostly as a teaching/learning (“pedagogical”) tool.

The three segments are: 1) the Pre-Root; 2) the Verb Root; and 3) the Post-Root. Consider:

We will discuss these segments and their sub-parts in order of appearance in a complete verb, from left to right.

First: The Pre-Root Segment

The Pre-Root Segment includes two types of morpheme: 1) Prepronomial Prefixes, and 2) Pronomial Prefixes (also called “Pronomials” or just “Pronouns”). It is everything that comes before the “Verb Root”—which is the portion of the verb that actually carries the specific meaning of the verb itself.

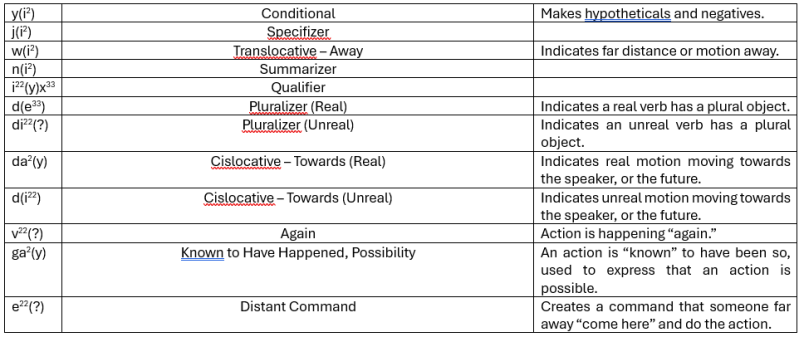

Prepronomial Prefixes. These are Prefix morphemes that modify verbs in a wide variety of ways. The only thing they all have in common is they all come before Pronomial Prefixes—hence the name. They are diverse in the kinds of meanings and modifications they make to the verb—but all in all, there aren’t very many of them. Here they are:

Ignore the scary looking parentheses and numbers and symbols for now. You’ll learn to read those soon. The explanations in this table are extremely simplified, but should give you a sense of the different kinds of things Prepronomials can do. There are three points of good news here:

- There aren’t very many, so there’s not a whole lot to memorize.

- Most of them serve pretty simple functions, and are not difficult to learn or understand. The only obvious exceptions (in my opinion) are the Summarizer /ni2/ and the Qualifier /i22(y)x33/. Those two are different beasts altogether, but we’ll get there in time.

- Because of the first two points, Prepronomials as a whole are probably one of the easier subtopics within verb conjugation.

Prepronomials are not generally necessary to make a complete (fully conjugated) Cherokee verb. You will often form complete verbs without using any of them. However, whenever you are trying to convey some specific meaning for which a specific Prepronomial is necessary, then you will have to use the relevant Prepronomial.

Also, some verbs require a specific Prepronomial in order to be fully understood or recognized—some verbs are understood as inherently plural, for example, and those verbs must be formed using a Pluralizer Prepronomial in order to be understood correctly. Some verbs (like the verb for “sending” something) have an inherent “motion away” quality, so those verbs must be formed using the motion away Prepronomial. These are referred to as “frozen” or “bound” Prepronomials. If you see a verb in the CED that already has a Prepronomial inflected onto it, it is an example of a “bound” Prepronomial.

You can put as many Prepronomials on a verb as you want, in theory. In practice, there are some Prepronomials that “can’t” be used together because they have incompatible meanings. For example, if you tried to use the “motion away” and the “motion towards” Prepronomials on the same verb, the result would be nonsensical. There is also a pragmatic limitation—the more Prepronomials you use, the more difficult your verb is to say and understand. So, although there is technically no a limit on how many Prepronomials you can use, in practice most speakers rarely use more than three Prepronomials per verb.

As we work our way through the segments of the Cherokee Verb, we’re going to add one piece at a time until we’ve built a complete, fully conjugated example. We’re starting with this one, the Translocative “motion away” Prepronomial:

/ wi2 /

Prepronomials come, unsurprisingly, before “Pronomials.” Pronomials are the second kind of Morpheme found in the Pre-Root Segment of a Cherokee Verb:

Pronomial Prefixes. These are the “pronouns” of the Cherokee language—equivalent to English words like “he, him, she, her, I, we, you, they” and so on. In Cherokee, Pronouns do not come in the form of words. Instead, they are Prefix morphemes that must be attached to a Root. Pronomials are mandatory to create a complete Cherokee verb. Every single verb correctly conjugated in the Cherokee language must include a Pronomial Prefix.

Pronomials are a particularly difficult aspect of Cherokee Conjugation for most English-speaking students. I will be treating them more in-depth in a separate essay, so we won’t be diving too deep into them here. For now, you just need to know the following basic points:

- Pronomial Prefixes are the Pronouns of Cherokee language.

- Pronomial Prefixes are necessary in a correctly conjugated Cherokee verb.

- Unlike English Pronouns, which are closely associated with expressing gender (the difference between “he” and “she,” for example), Cherokee Pronouns do not denote gender at all. There is absolutely no distinction between “he,” “she,” and “it” in Cherokee.

- Each Pronomial Prefix indicates a specific Subject-Object relationship—that is to say, every single Pronomial denotes both the do-er of the action (Subject) and the person or thing receiving the action (Object).

- There are a lot of distinct Prepronomial Prefixes to learn.

This Pronomial we’ll be using to build our complete verb is /gv21(y)/, which denotes a Singular 1st Person Subject and a Singular 2nd Person Object. In other words, it means “I” am acting on “You”—for this reason, it’s often called the “I to You” Pronomial. If we put it with our Prepronomial, we get:

/ wi2 / + / gv21(y) /

wi2gv21(y)

Listening Note – How to Identify the Pre-Root Segment. The Pre-Root Segment is relatively easy to identify—it comes first, so it’s the first thing you hear when someone makes a verb. Additionally, Pronomial Prefixes almost always include the “Lowfall” / 21 / tone, which is a quickly pronounced downwards slip in tone—its primary purpose is precisely to indicate where the Pronomial is. This gives listeners an important “checkpoint” to listen for. The Pronomial Lowfall tone helps listeners hear the “seam” between the Pre-Root segment and the next Segment—the Verb Root. It helps highlight the beginning of the Verb Segment that denotes the specific action occurring—it flags the beginning of the truly “verbal” part of a Cherokee verb. Fluent Cherokee speakers, especially older folks, are highly sensitive to this specific tone indicator and will be listening for it.

Second: The Verb Root Segment.

The Verb Root contains every Morpheme category that is necessary to fully convey the verb action as it is defined in the dictionary. This segment expresses the specific verb action itself—the Segment that actually describes the action that is happening. The other segments can be thought of as subordinate to this Segment in that they serve primarily to modify the action expressed in the Verb Root. This is the “verb” part of a Cherokee verb, so to speak.

The Morphemes included in the Verb Root Segment are, in order: 1) Reflexive Infixes, 2) Verb Stems, and 3) Adverbial Suffixes. If you were to change or modify any of these parts, it can often change the verb’s overall meaning so much that an entirely different English verb is necessary to accurately reflect the change. That is to say, changes to the parts of this Segment often change the overall translatable meaning of a Cherokee verb.

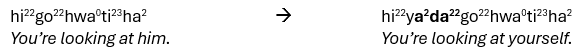

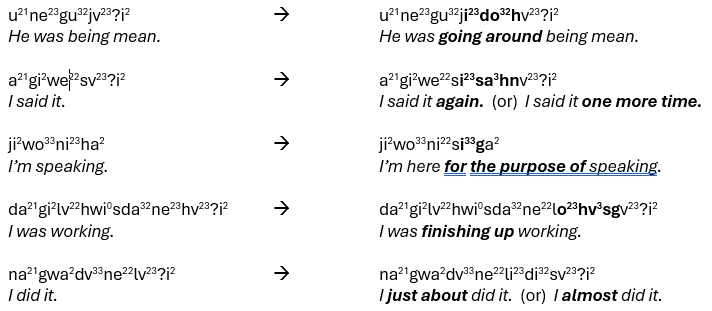

Reflexive Infixes. These come directly between the Pronoun and the Verb Stem, and there are only two of them: 1) the “Outsourced Reflexive” /a2d(a22d)/; and 2) the “Insourced Reflexive” /a22l(i2)/.

The term “Reflexive” is typically used to describe a situation where the Subject of a verb (the one acting) is the same as the Object of the verb (the one being acted on). It means someone is acting on themselves—English examples include phrases like “he’s washing himself,” or “she’s looking at herself.”

However, the term “Reflexive” is being applied kind of loosely here—Reflexivity in Cherokee is a different beast, and these morphemes are a difficult topic for many learners. Here’s the most clear-cut explanation of their differences I’ve heard, given to me by JW Webster:

/ a2d(a22d) / Outsourced Reflexive. This has a basically “true” Reflexive meaning—it means the Subject and the Object are the same. It also carries a more specific meaning that the verb action is being direct “outwardly,” or is done with the use of some tool or the help of another person—this is why it is called “Outsourced.”

/ a22l(i2) / Insourced Reflexive. You can think of this as “Reflexive-lite.” Instead of indicating the Subject and Object are the same (true Reflexivity), this Infix “de-emphasizes” the Object altogether—meaning it can make verbs Intransitive (“Intransitive” verbs are verbs that have no Object). It can also denote a meaning that the verb action is being done without the use or help of any external thing—no tools, objects, or helpers, using only the body or internal faculties of the one doing the action.

So each Infix has two meanings—a “Reflexivity”-related meaning that affects the Subject/Object information of the verb, and a “Source”-related meaning that illustrates how the action is accomplished. Many verbs in the CED are presented with one or the other Reflexive Infix already included—these verbs require the given Reflexive Infix to accurately convey the specific meaning given by the dictionary translation. The difference between one Infix or the other often means a complete change in the way the verb is translated:

For this reason, it’s best to think of Reflexive Infixes as part of the Verb Root when you see them—i.e., that they are necessary to form the intended meaning of the verb. The verb itself isn’t the same if you add, remove, or change them. In the “grinding” example above, I had to pick totally different English verbs in order to accurately reflect the change caused by the shift in the Reflexive Infix—the original root meant “to take one’s time grinding something,” but the Outsourced results in “preparing/cooking,” and the Insourced causes it to translate as “eating/dining.”

We’re not going to add either of these to the word we’re building—so let’s move on.

Verb Root. This is the morpheme (or usually, a string morphemes) that describes the specific verb action itself, plus smaller morphemes called “Root Suffixes” that are best thought of as part of the Verb Root. There’s not much more to say—this is the part of a verb that truly is the verb. This is the core. I’m going to discuss the topic of Verb Roots and their smaller parts with much greater detail in later essays. For now, just note:

- Verb Roots can come in up to five different “Stem Forms”—they are the Present Continuous, Incompletive, Completive, Immediate, and Infinitive.

- The difference from one Stem Form to another is usually based on changes to “Root Suffixes,” which are small morphemes that usually come at the very end of a Verb Stem.

- You should think of the different “Stem Forms” as the foundation of Cherokee verb Tenses.

The Verb Stem we will be using is /hv3hn/, the Completive Stem Form of the Verb Root for “sending something:”

/ wi2 / + / gv21(y) / + / hv3hn /

/ wi2gv21hv3hn /

Let’s take a break to parse our verb in its current, unfinished form:

- We know the verb action is going “away,” from the Prepronomial: / wi2 /

- We know the verb action is being done by “me” to “you,” from the Pronomial Prefix: / gv21(y) /

- We know the verb action itself is the act of “sending something,” from the Verb Root: / hv3hn /

The final sub-part of the Verb Root Segment is:

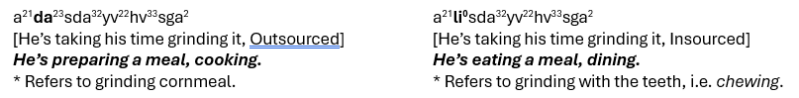

Adverbial Suffixes. These are a group of suffixes that slightly change the meaning of the verb itself, usually in an “adverb-like” way—hence the name Adverbial Suffixes. That name is JW Webster’s terminology, and the terminology I think works best. These suffixes have also been called “Non-Final Suffixes” in the CED, and “Aspect Suffixes” in Brad Montgomery-Anderson’s Cherokee Reference Grammar. Here’s some examples:

These suffixes are “modular,” like most Cherokee morphemes. By “modular” I mean they can be used creatively—or “productively,” to use a Linguistic term—to create new words and phrases on the fly. If you use one to modify a verb, your meaning will be understood by speakers even if they’ve never heard that Adverbial Suffix with that verb before.

Adverbial Suffixes aren’t the only way verbs can be modified in this “Adverbial” way—for any Adverbial Suffix construction, there are other ways to say the same things using helping words or even other verbs:

Always remember—in a Polysynthetic language, there are usually many different ways to say something. Picking which you prefer is often a matter of upbringing or even personal style. For second language learners, the decision can (and probably should) be based on convenience. If you have multiple ways to say something—and you usually will—you should practice using the methods you find easiest to use and remember. For most English speakers, Adverbial Suffixes will be much harder to use comfortably than most other options. So don’t feel too pressured to master these or use them productively right away—you can treat them as an “advanced” topic for you to master later. In fact, this attitude may not be limited to second-language learners. JW Webster tells me productive, off-the-cuff use of Adverbial Suffixes (as opposed to other methods) is something he specifically associates with highly eloquent, highly refined Cherokee speech patterns. So don’t feel pressure to master them or work them into your speech in the early stages of learning.

That said, you should study them and learn to recognize them as soon as possible even if you don’t practice using them productively. Why? Because many, many, many Verb Roots directly incorporate them. By “directly incorporate,” I mean that—despite the generally modular character of Adverbial Suffixes—many Cherokee verbs require a certain Adverbial Suffix to fully express their given dictionary meaning. If you try to drop the Adverbial Suffix from such verbs, they no longer mean what the dictionary says they mean.

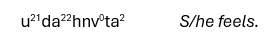

Here's an example to illustrate what I mean: the relationship between the verbs for “feeling” something and “thinking about” something.

Cherokee makes no distinction between “thinking” and “feeling.” Both are understood to take place within the mind, which is why the morpheme for “mind” /a2hnv0t/ can be found in the middle of this word. I won’t parse every morpheme here, but the closest literal translation which accounts for every discreet morpheme included is “s/he is minding herself right now.” It is used by Cherokee speakers analogously to how English speakers use the verb “to feel.” So that’s the translation used in the CED.

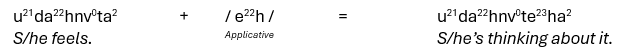

One of the Adverbial Suffixes, called the “Applicative” or sometimes the “Benefactive,” denotes that an action is being done “for” or “to” something or someone else. In the Incompletive and Present Stem Forms, this Adverbial Suffix takes the form /e22h/. If we add this Adverbial Suffix to the verb above, it changes the meaning in a big way:

More literally, the new verb translates as “s/he’s applying-mind-to-something-ing herself right now.”

In the CED, these two words are listed as completely separate verbs. They have their own separate entries, index forms, and example sentences. In my writing I often refer to this as a change in the “translatable meaning” of a word—meaning the inflection applied has changed the meaning of the Cherokee verb enough that it must be translated into English using a different word altogether. But is it really a different verb? An English speaker hears a fundamental, real difference between “feeling” and “thinking about” something—is the same true for a Cherokee speaker hearing udahnta and udahnteha? This illustrates an important lesson: be careful not to get too hung up on the specific English definitions provided by Cherokee dictionaries. Strive to hear and understand Cherokee on its own terms. Look for patterns.

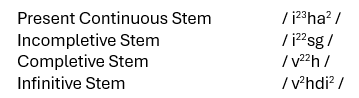

Because Adverbial Suffixes are often directly incorporated into a verb’s root, especially as presented in the dictionary, many verbs show predictable patterns across their Stem Forms. Stem Forms are another topic for another essay later on—I’ve already mentioned them once when I said that each Verb Root can have up to five different Stem Forms. This is also true for Adverbial Suffixes—each Suffix has up to five different Stem Forms, and this is why you can use them to learn and recognize patterns. For example, here are all the Stem Forms for the Processive Adverbial Suffix, which denotes an “in the process of doing the verb” meaning:

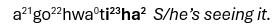

If you have these patterns memorized, it will help you shortcut the process of memorizing the different Stem Forms of any verb in which you recognize the Processive Suffix (and by the way, there are a ton of Cherokee verbs that use the Processive). Take this verb, for example:

If you know the Processive Adverbial Suffix when you see this verb for the first time, you won’t even need to be shown the example Stem Forms for the verb to guess what they are. They will, in almost all cases, align with the Suffix’s Stem Forms:

If you didn’t know how to recognize these patterns, you’d have to treat every Verb Stem Form as a separate data point that has to be separately memorized. If you know the pattern, you just have to remember the pattern. So knowing your Adverbial Suffixes will make the process of learning and memorizing new verbs much, much easier.

I’ve gotten a bit off-topic. Let’s bring it back to the subject at hand—the segments of the Cherokee verb. To refresh your memory, the Adverbial Suffixes are part of the “Verb Stem,” the middle (second) segment of a fully-formed Cherokee verb. Anyways, let’s pick up where we left off by adding the Incompletive Stem of the Pre-Incipient Adverbial Suffix /i23di32sg/, which denotes a “just about to do the action” meaning to the verb we were building from before:

/ wi2gv21hv3hn / + / i23di32sg /

/ wi2gv21hv3hni23di32sg /

So far, our verb is still incomplete, but at this point we know:

- The verb action is going “away,” from the Prepronomial: / wi2 /

- The verb action is being done by “me” to “you” from the Pronomial Prefix: / gv21(y) /

- Something is being “sent” from the Verb Root: / hv3hn /

- The verb action was “just about” to happen from the Adverbial Suffix: / i23di32sg /

Now we move to the third and final segment of a Cherokee Verb: the Post-Root Segment.

The Post-Root Segment.

The Post-Root Segment contains only two parts: 1) Tense Suffixes, which are mandatory; and 2) Clitics, which are not.

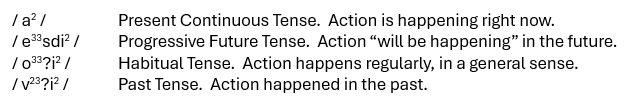

Tense Suffixes. Unsurprisingly, these are Suffix Morphemes that indicate a verb’s Tense—that is to say, they denote the time in which the verb’s action is happening—past, present, future, and so on. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of Tense Suffixes with generalized descriptions of their meaning:

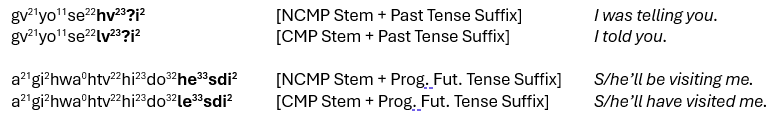

Understand this as early as possible: Tense Suffixes aren’t enough, by themselves, to fully communicate the Tense of a complete verb. The full “Tense” of a complete Cherokee verb is indicated by the interrelationship between the Verb Root’s Stem Form and the Tense Suffix. Again, we’ll talk about Stem Forms in another essay later—for now, I’ll illustrate what I mean like this:

Some Tense Suffixes are only used with certain Stem Forms, so Stem Form can be understood as preceding Tense, or laying the foundation of the verb’s Tense. But generally speaking, most Tense Suffixes can be used with any Stem Form, and you shouldn’t get into the habit of associating specific Tense Suffixes with specific Stem Forms.

Back to the verb we’ve been building, which is in an Incompletive Stem Form because we used the Incompletive Stem of the Adverbial Suffix. The Tense Suffix is the very last piece we need to form a complete, fully translatable, fully intelligible Cherokee verb—we’re going to use the Past Tense /v23?i2/. Once I’ve added it to our word, we’ll be able to fully translate the verb we’ve been building:

/ wi2gv21hv3hni23di32sg / + / v23?i2 / = wi2gv21hv3hni23di32sgv23?i2 I was just about to send it to you.

We now have a completely conjugated, fully formed, usable verb in the Cherokee language.

Quick Review: Before we move on, now is a good time to specifically identify which morphemes are absolutely mandatory to form a complete verb:

- Pronomial Prefixes.

- Verb Root (including any Reflexive Infixes or Adverbial Suffixes that are directly incorporated into the Verb itself—i.e., necessary to accomplish the intended meaning of the Verb).

- Tense Suffix.

Every single Cherokee verb requires, at a bare minimum, these three parts. Everything else (Prepronomial Prefixes, additional Adverbial Suffixes, Clitics, etc.) are optional—unless you’re trying to craft a specific meaning that makes any of those other parts necessary.

So we’ve covered everything you must have for a complete verb, and many things that are optional. But there’s still one last verb part to discuss—Clitics. But, we’ll keep it brief.

Clitics. Also called “Post-Fixes,” this is a collection of interesting morphemes that can (and are) used on basically every kind of word in Cherokee. You’ll see them on nouns, verbs, adjectives—anything and everything. No matter what kind of word they attach to, they will always come at the very end. They are often used to fine-tune word meanings with different kinds of meanings, moods, emphases, and so on. They are also used to change sentences into questions. Some serve the function of conjunctions.

Here are a few common examples of Clitics that demonstrate the different kinds of uses they have:

CONCLUSION

Hopefully this gives you a big-picture idea of what Cherokee verb conjugation is like—a very general introduction of how the process of building and understanding a Cherokee verb works. You may be feeling overwhelmed or discouraged by this topic. To that, I’ll say this: if verb conjugation seems like a huge, scary, difficult thing, that’s because it is. This is by far the biggest and most important topic for learners to tackle.

But here’s the good news: everything else is genuinely easy by comparison. Learning how to form, use, and understand verbs is a mountain to climb, for sure. But it’s the only thing like this, the only topic that’s this huge. Now you just have to put in the work and climb it. Once you start learning, verbs should your primary focus until you feel comfortable enough to move on to other things. When you get there, you’ll be shocked—underwhelmed, even—by how easy everything else seems.

By: J.R. Lancaster, a second language learner. May contain mistakes.

Add comment

Comments